The origins of the Guérin surname, whether with or without l’accent aigu, are ancient. As I pursued the mystery of my own family origin, numerous sources kept pulling me to France, Ireland, Québec and elsewhere. Early 20th century US census records for Massachusetts showed an almost equal number of “Canadian French” and “Ireland” birthplaces for people named Guerin, or some spelling derivative thereof. (The numerous spellings and pronunciations of Guerin have been a source of mirth and frustration throughout my life, never mind having to wade through them all in countless civil and religious records.) While I was able to track my own family origin back to Québec, the foundation of the Guerin surname’s dual origin continued to intrigue me.

Of Irish Origin

According to the book “The French Guerins of the Glen: A Saga of Three Centuries” by Thomas Guerin (Montréal 1963), there are two sources of the Guerin surname in Ireland: an old Irish tribe and a migration of French Huguenots in the late 1600s.

The Irish tribe in question was the O’Gearain tribe. The name comes from:

… the name of a family of the ui Fiachrach, the son of Eochaidh Muighmheadhoin, King of Ireland in the Fourth Century. Fiachrach was the brother of Niall of the Nine Hostages and father of the last pagan King of Ireland. Through the course of time they became known as O’Gerane, O’Guran, Gearan, Gearn, Gearns and even sometimes as Guerin. They are reputed to have had a rath or fort on Lake Gowna. Elizabeth conquered them, uprooted them and then planted them in other parts of Ireland. Many appear to have been placed on the West Coast of Kerry where their descendants still are to be found today.

Of French Origin

Saint Guérin

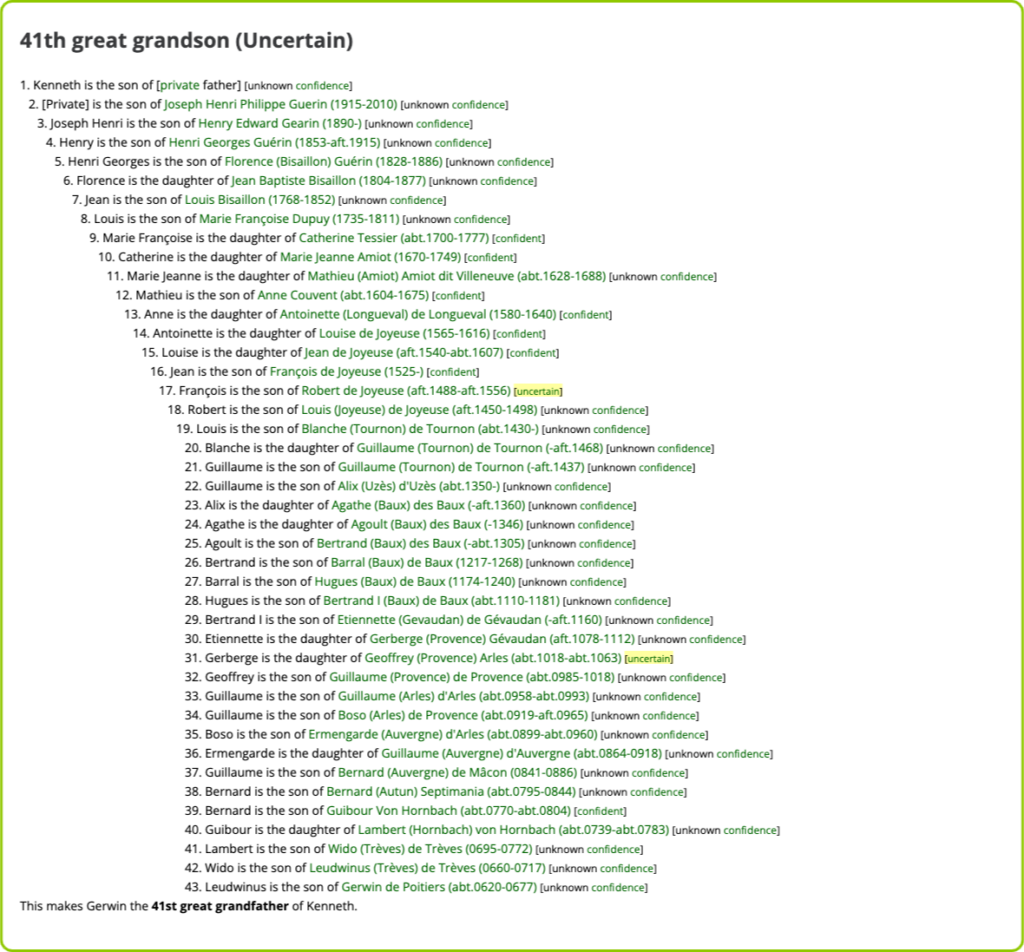

One of the earliest known records of the name Guérin in France comes from Saint Warinus of Poitiers, where Guerin is an alternate form of Warinus, as are Gerinus and Varinus. On Wikitree, his profile is under Gerwin de Poitiers and I am a direct descendent.

In the online transcription of Charles Cawley’s “Medieval Lands”, the encyclopedia of territories in the medieval western world and the royal and noble families which ruled them, Warinus, listed as Garinus, is listed among the Merovingian Counts of the 7th Century (3rd block of lists, Item 2b).

Guérin de Montglave

Another Guérin of the Early Middle Ages was one Guérin de Montglave. There is an interesting story about him in “Chess History and Reminiscences” by Henry Edward Bird, published in 1893. In this book, the author relates a story of how Charlemagne lost his kingdom to Guérin de Montglave, one of Charlemagne’s courtiers, over a game of chess. In this story, both players fancied themselves as excellent chess players and Charlemagne’s confidence was so high that he wagered his entire kingdom over the match. When Guérin bested Charlemagne over the board, the emperor laughed it off. However, the victor would not be denied the spoils of his victory. A wager had indeed been placed. To placate Guérin, he was given all rights to the city of Montglave (today’s Lyon), then in the hands of the Saracens. It was up to Guérin de Montglave to raise an army and capture the city, which, according to “Œuvres: Volume 4, Guérin de Montglave” by Louis Élizabeth de Lavergne de Tressan (Paris, 1824), he did indeed do. Not only did he defeat Gasier, the sultan in charge of the city, but he also wed Gasier’s daughter, Mabilette, after she was baptized as a Christian. Together they ruled Lyon and lived happily ever after. Or so the story goes…

Frère Guérin

While the actual existence of Guérin of Montglave may be in doubt, one Middle Ages Guérin whose origins are quite clear is Frère Guérin. This Guérin was born around 1157 at Pont-Sainte-Maxence in France and passed away in the year 1227. Over his lifetime, he became a knight of the Ordre de Saint-Jean de Jérusalem, participated in the Battle of Tibériade in 1187, became the first garde des sceaux in French history under King Philippe II Auguste in 1201, became Bishop of Senlis in 1213, was a major participant in the Battle of Bouvines in 1214, and became Chancelier de France in 1223.

The Battle of Bouvines, 1214

Being a medieval battle, the historicity is often composed of storytellings of mixed value, each one containing various embellishments. Of the result of the battle, there is no doubt. On 12-Jul-1214, King Philippe II Augustus of France defeated the combined forces of Otto IV, the count of Flanders, and King John of England, near Bouvines in northern France. To some historians, this battle cemented the nation and legacy of France itself.

As to Frère Guérin’s role in this battle as a holy knight, only a few accounts tell of his exploits. According to the account penned by a member of Robert of Bethune’s entourage (source: De Re Militari),

Brother Guerin came to the King at a church called Bouvines, near Cysoign, which the Queen had once visited. He found him off his horse at a place where he had refreshed himself with bread and wine. He asked him: “What are you doing?” “Well,” said the King, “I have eaten.” “That is good,” said Brother Guerin, “and now you need to arm yourself because those on the opposite side do not, on any account, want to postpone the battle till tomorrow but they want it now. Thus you must do likewise.”

It was Sunday, and because of this the King would have preferred the battle to be postponed till the morrow for the honor of the day. But when he saw that there was no other way, he put on his armor, entered the church, made his orisons, and was soon finished praying. Then he climbed on his horse and did not appear frightened anymore as he decided and ordered his affairs very wisely and assuredly and without any panic, and had everyone, knights and others, called to return to their battalions. I must tell you that most of the host had already passed a bridge spanning a small river and several pavilions had already been set upon the other side of the bridge in a meadow where the King had planned to spend the night.

A second account penned by William the Breton, personal chaplain and advisor to King Philippe II Augustus and who was present at the battle, compares favorably with the previous account.

The King neither knew nor thought his enemies were thus coming after him. It so happened by chance or by the will of God that the Viscount of Melun along with other lightly ‘armed knights detached himself from the King’s host and rode toward those parts from which Otto was coming. And, detached also from the host and riding with him was Brother Guerin, the Elect of Senlis (Brother Guerin, we call him, because he was a practising brother of the Hospital and still wore its habit), a wise man, of sound counsel and with marvelous foresight for things to come. These two went away from the host for about three miles and rode together till they climbed a high hill from which they were able to see clearly their enemies’ battalions moving fast and in fighting formation. When they saw this, the Elect Guerin left immediately and made haste to return to the King, but the Viscount of Melun remained on the spot along with his knights who were rather lightly armed. As soon as he reached the King and the barons, the Elect Guerin told them that their enemies were fast arriving in battle order and that he had seen the horses covered, the banners unfurled, the sergeants and the foot soldiers up front which is a sure sign of battle.

As to Frère Guérin’s activities during the battle, William the Breton’s account continues:

The first assault of the battle did not occur where the King was, as; before those in his echelon and proximity could start the fray, others were already fighting against Ferrand and his people on the right side of the field without the King being aware of it. The first line of the French battalion was positioned and organized as we have described above and extended 1,040 paces across the field. In this battalion was Brother Guerin, the Elect of Senlis, fully armed, not to do battle but to admonish and exhort the barons and other knights to fight for the honor of God, of the King, and of the kingdom, and for the defense of their own welfare. There were also Eudes, the Duke of Burgundy, Mathew of Montmorency, the Count of Beaumont, the Viscount of Melun and other noble combatants, and the Count of Saint-Pol whom some suspected of having made agreements with their enemy in the past. And because he was well aware of this suspicion, he quipped to Brother Guerin that the King was to find him to be a good traitor today. In this same battalion were 180 combatants from Champagne which the Elect Guerin had organized: he moved some of them from the front to the rear as he felt them to be cowardly and fainthearted, while those he felt to be courageous and eager to fight, in whose prowess he had faith and confidence, he put in the first echelon and told them: “Lord knights, the field is large, spread yourselves out so that the enemy does not surround you and because it is not fitting that some become the shields of others. Rather, arrange yourselves in such a way that you can all fight together at the same time, all in one front.” After he said this, he sent ahead, on the Count of Saint-Pol’s advice, 150 mounted sergeants to start the battle. He did this with the aim that the noble combatants of France, whom we have named above, would find their enemy somewhat agitated and worried.

A continuing of the account reports that the French right wing, commanded by Frère Guérin, was the first of the three to break the enemy’s lines and capture their opposite leader, Ferrand. Now without an active adversary, the victors turned left, hitting Otto’s center wing in the flank and coming to the aid of their king, Philippe, who had almost succumbed to the enemy during his part of the battle. Sweeping onward across the battlefield, the victorious knights fell upon the flank of the enemy’s right wing, commanded by the archtraitor, Renaud of Boulogne, who was captured and spared by Guérin in the nick of time:

… as he (Renaud) was slow in getting up from the ground, waiting in vain for help and still hoping to escape, a boy [a commoner] named Cornut, one of the servants of the Elect of Senlis, and walking ahead of the latter, a man strong in body, arrives holding a deadly knife in his right hand. He wanted to cut the count’s noble parts by plunging the knife in at the place where the body armor is joined to the leggings, but the armor sowed into the leggings will not separate and open up to the knife, and thus Cornut’s hopes are thwarted. However, he circles the count and looks for other ways to reach his goal. Pushing the two whalebones out of the way and soon pulling off the whole of his helmet, he inflicts a large wound upon his unprotected face. He was already getting ready to slit his throat; no one was holding him back and if it had been possible he would have killed him. The count, however, still resists him with one hand, and does his best to repulse death as long as he can. But, finally arriving at a full gallop, the Elect of Senlis pushes the threatening knife away from the count’s throat and himself pushes away the arm of his servant. Having recognized him, the count cries: “Oh, kind Elect, do not let me be assassinated. Do not suffer me to be condemned to such an unjust death, so that this boy could rejoice to be the author of my destruction. The King’s court would condemn me much better; let it inflict on me the punishment I have incurred.” He says this and the Elect of Senlis answers him in these words: “You will not die, but why are you so slow to get up? Stand up, you must be presented to the King right away.”

So describes the actions of Frère Guérin during the Battle of Bouvines, a battle that historian Alistair Horne called, in his article in Military History Quarterly, Vol 12, No. 2, “The Battle That Made France”.

Frère Guérin as Archivist & Chancellor

On 05-Jul-1194, 20 years before the Battle of Bouvines, King Philippe’s royal baggage was seized by Richard “Coeur de Lion” (Lionheart) in the Battle of Fréteval. In this baggage, laden with money and treasure, was King Philippe’s royal seal, tax account books, and royal charters, the latter being proof of the legitimacy of his kingship. In 1220, Frère Guérin was entrusted to collect and/or recreate these lost items. Based on the work of the Grand Chamberlain of France, Gauthier de Namours, and with the assistance of Étienne de Gallardon, he began the creation of the Trésor des Chartres. From this point onward, Guérin and his scribes ensured that there would be copies of all important royal and national documents so that any loss to the originals would not be fatal. Based on this work, he can be considered as the founder of the National Archives of France.

In 1223, Guérin became Chancellor of France and was ordered that he would henceforth sit among the Peers of the Kingdom. He would occupy this position until his death in 1227. He was buried in the Abbey of Chaalis, where there was a tomb with his reclining statue; his head resting on a cushion held by two angels; his feet were wedged on a lion; his hands were gloved, the top embellished with ornaments, his right hand raised as if to bless, and the other holding the bishop’s cross. The abbey was sold and demolished during the French Revolution, its tombs and statuary lost to time.

Guerin as Surname

While these Guerins show very early uses of the name, it is not a surname as we know it. The use and evolution of surnames is a complex topic left to more scholarly works than this one. In Europe, which is the origin of names Guerin, however, early surnames usually fall into one of three categories: occupation (Smith, Baker), location (Hill, Green) and “son of” (Jackson, Fitzpatrick, etc). While the origins of Guérin may be lost to the mists of time, the surname probably falls into the first category of occupation. While some family surname websites have hypothesized that “guérin” translates from Old French as “to watch or guard”, a translation from modern French is “healer”.

The Guerin Surname in Ireland

In the 1600s, as the French Huguenots were being driven out, a man by the name of Gaspard Guerin appears in Ireland, the first of that surname to appear. His name appears in a will that was proven in Charleville, County Cork in 1670, the only such record of his existence. From “The French Guerins of the Glen”:

Gaspard Guerin is only interesting because he is the first person of the name to appear in that part of Ireland in a place which is only fifteen miles from Bruff, County Limerick, where the Guerins settled only fourteen years after his death… There has been found but one entry which would indicate that he left a family. It appears in the records of the French Huguenot Church at Portarlington, Queen’s County, and refers to a marriage of July 2nd, 1710 of André de Lord to Margaret Choppy. He is described as ‘fils de Louis de Lord et de Gasparde Guerin’. The feminine form of the name Gaspard is very rare.

As interesting as this is, it does illustrate that even the Irish Guerins had French origins, ancient tribal lines excepted.

The Guérin Surname in France

Given that the Irish Guerins came from France in the 17th century, it follows that the Guérin surname is older than that. Unfortunately, the origin of the Guérin surname in France cannot be traced to a single individual. Given that the introduction of surnames in Europe often followed occupational lines, the proliferation of French soldiers in that time period probably gave rise to a number of Guérins spontaneously.

The Guérin Surname in the New World

Being of primarily French origin, the Guérin surname came to the New World initially via French colonists to Québec and Acadie. Their stories, however, will have to wait for another day.