“This is a Pilgrimage for You”

No sooner had Claire given voice to my innermost thoughts, in the shadow of Evangeline at the Grand Pré National Historical Site, did the river of emotions, deeply held for decades, threaten to overwhelm me. My discovery of self, of history, of culture, had come full circle.

Looping Through Acadia

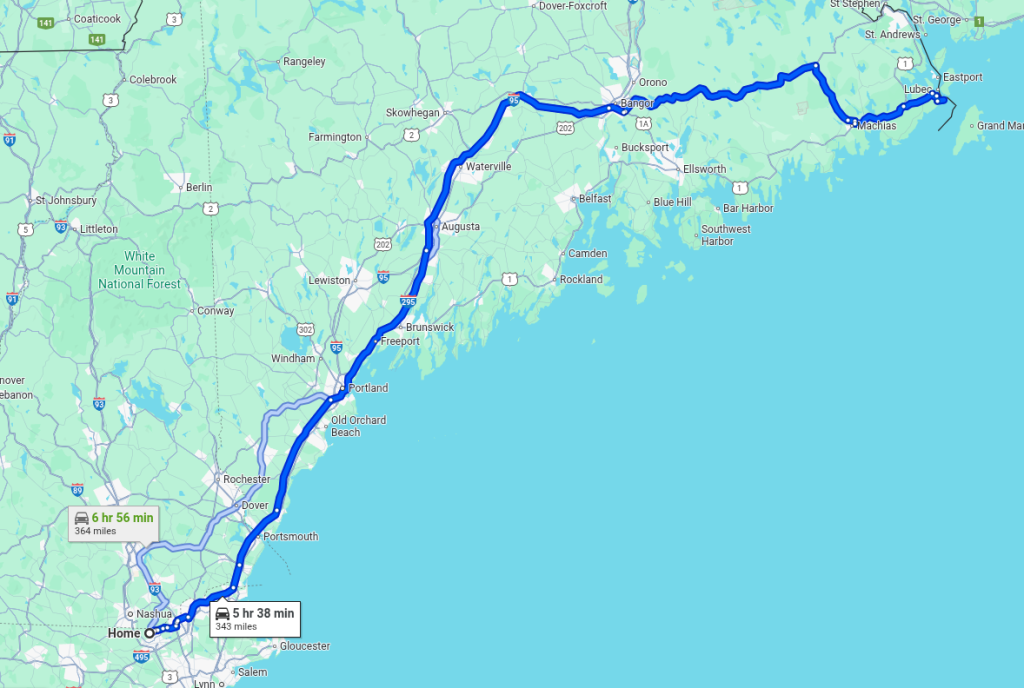

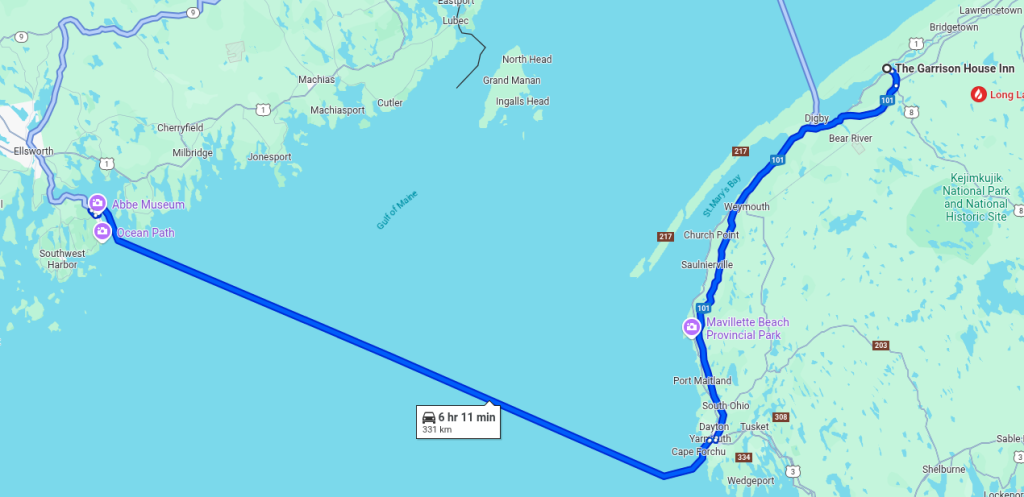

The Pilgrimage, aka the Acadian Loop, was an 8-day tour of eastern Maine, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. While the focus was Acadian history, we also made time for other natural and historic sites.

Day One: Monday, 18-Aug

This day was the longest day in terms of driving time, though the treks back and forth to Cape Breton Island would rival it. Claire and I began with an early morning start knowing just how long of a drive it was going to take just to get us in the vicinity of the attractions we wanted to see. After packing up the car with suitcases, backpacks, a cooler and an extra couple of bags for extra stuff that wouldn’t otherwise fit, we set off on our first exploration adventure in years.

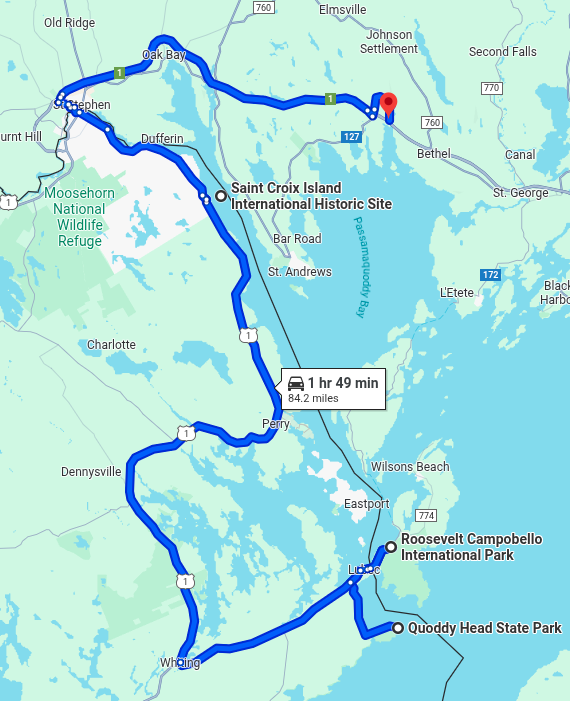

The first attraction was Quoddy Head State Park in easternmost Maine. In fact, its location in Lubec, ME makes it the easternmost point in the continental US. Besides being one of those geographic oddities that attract me when perusing maps, I’d always been attracted by those signs on the highway pointing the way to other locations when I’d reached the furthest point of any trip. “Just go a bit further,” I could hear them whisper to me. Well, this was the trip for that, going further eastward then I’d ever driven.

Quoddy Head was over 5.5 hours away by car, not counting stops for food or bio breaks. The drive was an uneventful pleasant one over the usual route to Bangor via I-95, followed by a lengthy trip down Maine Route 9. Once I turned onto Route 9, I was now driving on new ground and the real exploration began. Route 9 in this part of Maine is quite scenic and quiet and the drive along this stretch of highway was enjoyable. After taking Maine Route 189 south to US Route 1 in Machias, we were now “in country”.

Quoddy Head State Park was our lunch stop, albeit a late one. The views were excellent from the vantage points the park offers. There were quite a few picnic tables everywhere and the lighthouse, while short and stubby compared to others, was a nice bit of candy-cane-striped history. There was an old pay station, but it didn’t seem to be enforced. At least there was no obvious signage stating that payments were expected. Still, I dropped some cash into the old-fashioned, ornate metal canister.

From Quoddy, we went to the Roosevelt Cottage on Campobello Island. This cottage was the seasonal cottage of the Roosevelt family. As Campobello is in Canadian territory, this was our first border crossing of the trip, of the day even, and we entered without incident.

The Roosevelt Cottage is part of a greater International Park which celebrates (celebrated?) the amicable relationship between the United States and Canada, a relationship marred by current events spawned via a near-constant stream of US-instigated blathering nonsense. The cottage and surrounding grounds were in excellent condition and the tour guide, while lacking enthusiasm for the subject (it was probably his 10,000th time giving the tour), gave us plenty of details and answered our questions fully.

From Campobello, it was time to return to the US and it should have been uneventful. I mean, it was for us, but not the guy in the work van with the New Brunswick license plates who was prevented from entering the US. We don’t know what happened and we didn’t ask, but I suspect that someone forgot their passport.

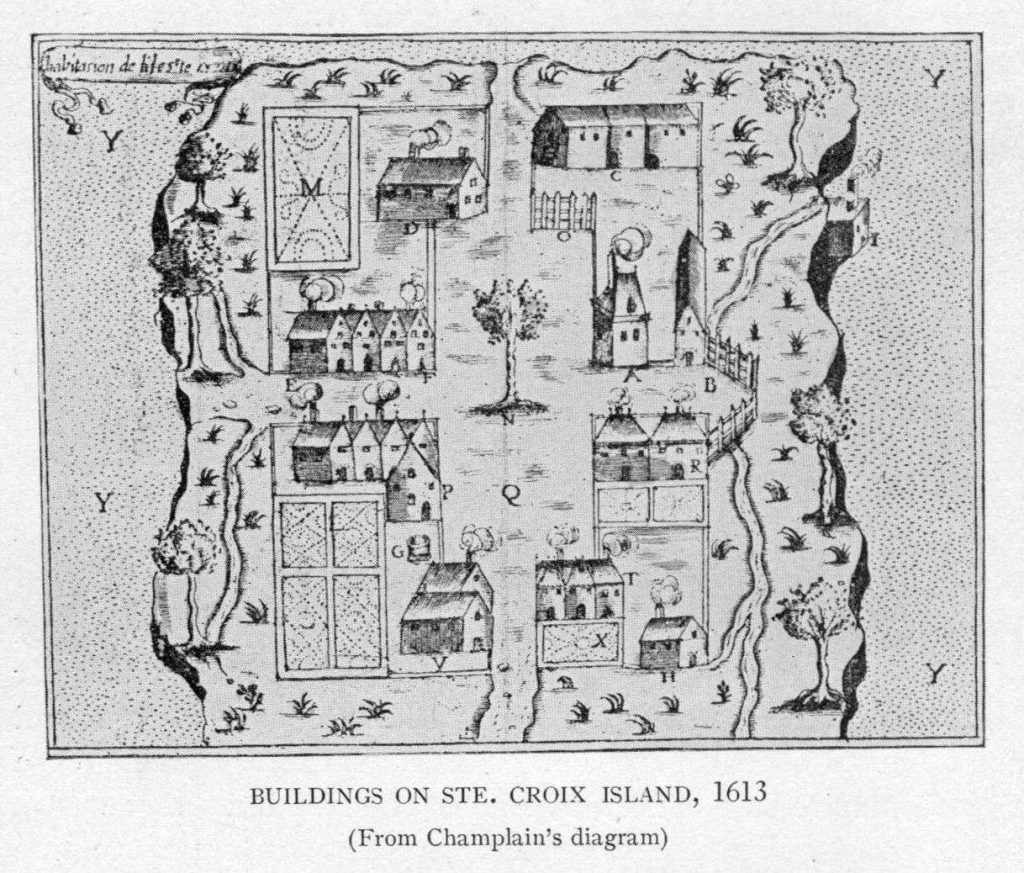

Our next stop was Saint Croix Island, or rather, the National Park Visitor’s Center on the mainland shore opposite it. Saint Croix Island was the initial landing place of the Acadian French in the New World. In 1604, the expedition of Sieur Pierre Du Gua de Mons landed on Saint Croix to establish a permanent settlement and fur trading center in the New World. It would be the first permanent settlement in Canada and the beginning of that great nation, though “permanent” turned out to be short-lived.

In 1604 Pierre Dugua, a French nobleman, organized a company of men that included young Royal Geographer Samuel de Champlain and Champlain’s uncle, Francois Grave Dupont. Dugua intended to colonize North America and trade with the Indians for furs.

…

In June they arrived at the tree-covered island in the mouth of the St. Croix River. They chose it because it offered protection from Indians and the English, who were also seeking a foothold in North America. “Vessels could pass up the river only at the mercy of the cannon of the island,” wrote Champlain. They determined the soil was good and they could trade with the Indians.

“Here seemed to be a Paradise,” wrote Champlain.

…

Winter came sooner than expected. It began to snow on October 6, and the cold was sharper and longer than winter in France. Many of the men were struck by a strange disease. Great pieces of superfluous flesh were produced in their mouths so they could take nothing but liquid. Their teeth got so loose they could be pulled out without pain. They couldn’t walk and had no strength. The majority could neither walk nor move.

They called the dreaded disease ‘mal de la terre.’

Thirty-five of the party of 79 died and more than 20 were on the point of death. They were buried in the cemetery shown on Champlain’s map. Years later their bones were exposed by erosion and taken to be analyzed. They showed signs of scurvy, which they probably contracted because they ate nothing but salted food.

(from St. Croix Island, The Lost French Colony of Maine)

When Dupont arrived in the spring with more men and supplies, it was decided that the island was no longer the paradise they thought it was. From there, the expedition established a new base at Port-Royal, on and near present-day Annapolis Royal in Nova Scotia. Port-Poyal would become the foundation of the French colony of Acadie.

Today, Saint Croix Island is in US territory, a result of a boundary dispute settlement with Great Britain in the 1800s. No one lives on the island. Considering today’s political climate, it is an unfortunate circumstance that the Cradle of Canada is on US soil.

After a very quick jaunt down an interpretive trail, where I got to catch a glimpse of the island, and a nice discussion with a very young park ranger from Georgia, it was time to head to our lodging for the night. As Claire and I are not folks who rough it, and that section of Maine caters to such accommodations, we crossed the border again into Canada and stayed at the Dominion Hill B&B in New Brunswick. While not a mistake, the breakfast was sub-par and disappointing. What I didn’t know, as I had booked the room weeks in advance, was that the B&B was under brand-new ownership, papers were signed within the previous week, and their breakfast prep routine was not fully established. Still, the room was comfortable and the grounds quiet, giving us a fitful sleep for our first night on the road.

For dinner, as the B&B didn’t offer any and was located outside of any town center, we drove down to the quaint seaside town of Saint Andrews. Unfortunately, the restaurants that the B&B owner suggested were closed; it was Monday after all. However, we managed to get a bite to eat at the Kennedy House where I had the first of many excellent seafood dishes.

Day Two: Tuesday, 19-Aug

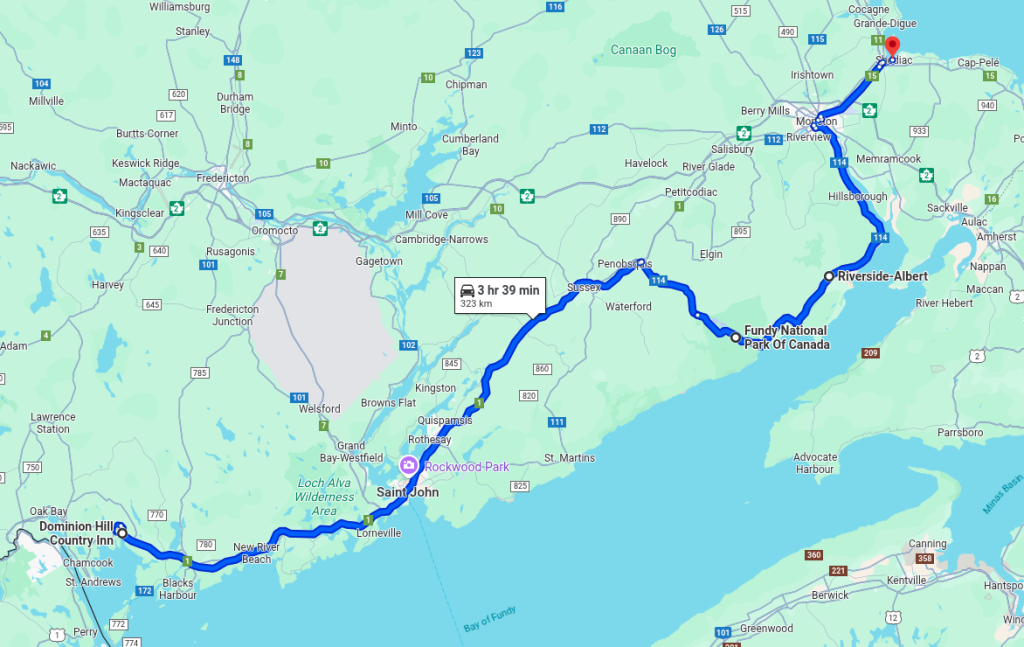

With such a long day of driving behind us, I purposely made the second day a shorter driving day. As we had also arrived at the B&B later in the day than our usual traveling routine, I opted for an earlier end of the day as well.

There were only two points of interest on this leg of this trip, although the itinerary allowed for four. The first would have been the city of Saint John, but as we were planning on returning to Saint John via the ferry from Digby on the last day, I decided to breeze through the city today and visit some sites then. Well… spoiler alert… plans changed later in the trip and we missed Saint John.

At Fundy National Park, we were greeted with two surprises. The first was that Parks Canada was not collecting admission fees to their parks. Claire and I didn’t pay a dime for any of the Parks Canada attractions we visited throughout the entire trip. Yay!

The second surprise was that all hiking trails in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia were closed due to wildfire danger with hefty fines for violating this. Awww… So much for hiking, although very short trails to beaches were exempt.

This shortened our time in Fundy considerably. That said, after a very good lunch at Tides Restaurant in Alma, we walked the beach during a very low Bay of Fundy tide and marveled at just how much the tide swings back and forth. It was a good way to stretch our legs.

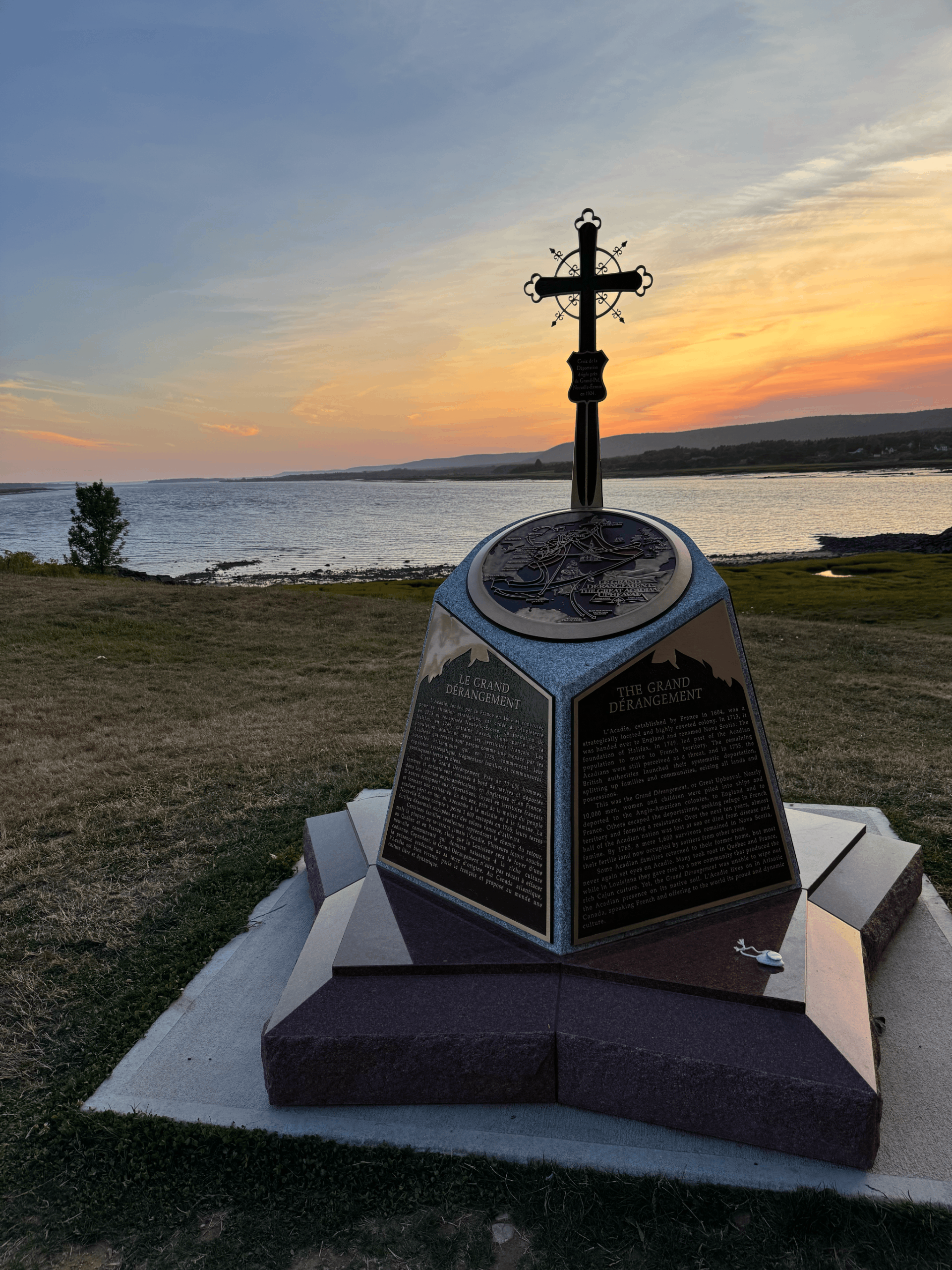

After that nice respite, we took to the back roads to the Chipoudy Acadian Monument in the town common of Riverside-Albert. Here, I was able to see and touch the roster of Acadian names who had settled in the French town of Chipoudy (now named Shepody). There I saw it: Martin dit Barnabé, my ancestor. His wife’s name, Granger, was not on the monument. Her family was still in Port-Royal at the time of the Expulsion.

The stop here was quick and it was time to get to the hotel. After a meandering drive along back roads to finally get back to the main drag, we drove through Moncton to Shediac.

The Hotel Shediac is a standard hotel with comfortable rooms and a restaurant/bar on site. It is situated just off the main street of the city. After checking in, Claire and I took a walk to the outside terrace of the Hôtel de Vieux Port for some drinks and snacks. Unfortunately, the hotel proper was closed due to a fire, but the outside terrace was still in operation. Apart from the ever-present bees flying around, it offered a casual ambiance and a comfortable place to enjoy a sip or two. One thing we noticed was that we were in a French part of town. You could see it in the signage and hear it in the accents. In fact, we passed by the Club Boishébert de Shediac on the way, which seemed to be a French/Acadian social club. A sign said they were open and if I was a braver soul, I would have gone in.

(For me, trying to converse in French is like building IKEA furniture. The parts are all there, I think, but the instructions are cryptic and the allen wrench is missing.)

Returning to the hotel, we had dinner and drinks at the bar and settled in for the night. Tomorrow would be a long day.

Day Three: Wednesday, 20-Aug

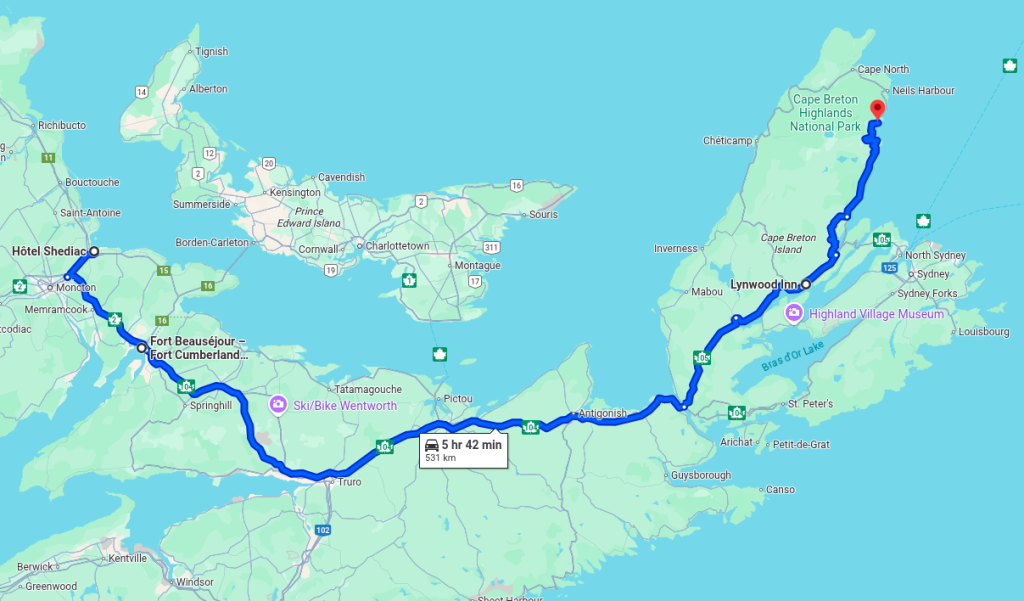

It would be a challenging day. Obstacles encountered at the beginning of a long day are more easily endured than those encountered towards the end. More on that later.

The day began with a quick stop at the local grocery store and a purchase of pre-made sandwiches so that we could eat on the road. It was the best thing we did.

Well, not quite. Fort Beauséjour proved to be an excellent stop. In 1755, this four-year-old fort on the border between French Acadie in current-day New Brunswick and English Nova Scotia became the front line in the opening shots of the French & Indian War, aka the Seven Years’ War. Its fall after a quick siege marked the beginning of the Acadian Expulsion.

It was here, in the region known as the Chignecto Isthmus, that Pierre Martin dit Barnabé, my ancestor, was taken by the British and sent to South Carolina with hundreds of other Acadians aboard the Endeavour. While it cannot be proven due to a lack of records, it is possible that Pierre was one of the Acadian citizens pressed into service by the French soldiers to help defend the fort during the siege. What is known is that his home and family were in Chipoudie, well away from the fort. After his forced deportation, Pierre’s family left Chipoudie and escaped inland to Québec. Whether immediately in the aftermath of the battle or some time later in the conflict is unknown. Eventually, Pierre made his way to Québec and reunited with his family in the L’Assomption area.

As to the fort itself, like the other historical sites we visited, Parks Canada has done an excellent job at restoration and providing information and guides to help answer questions. Claire and I spent some time with one of the guides who explained the purpose of the fort and the changes the British made when they took it over and renamed it Fort Cumberland.

After the two hours or so we spent at the fort, we were back on the road. Almost immediately, we entered Nova Scotia, where we would spend the rest of our vacation.

The trek both to and from Cape Breton was long and tedious. The terrain did not change much, which didn’t help. I will, however, say that driving in Canada was a serene experience. People drove the speed limit. They stayed in the right lane and only moved left to pass. They used their turn signals. In a most un-Massachusetts manner, I followed suit. Driving became a delight and not the usual white-knuckle, epithet-filled experience I was used to. However, it was still a long drive… made worse as we crossed the Canso Causeway onto Cape Breton Island.

We’d already eaten our sandwiches, but were getting hungry. It was mid-afternoon and had figured that we’d get to our cottage at Seascape Coastal Retreat in Ingonish at a reasonable time for dinner somewhere. That was until the ETA on the iPhone’s Maps app kept fluctuating from a time that was reasonable to something quite horrific. That’s when I saw the Car Accident icon on the map.

Take a look at a map of Cape Breton Island. There isn’t a wealth of routes on the island. There are hill ranges and the Bras d’Or Lakes and other natural barriers to transportation. So, when a section of Trans-Canada Highway 105 was closed due to an accident of some sort, we had to take a detour, once we got past the logjam of traffic at the initial set of rotaries / roundabouts that you hit once you get on the island. 15 miles later, and after driving the right-hand side tires on a hard shoulder on the minor residential road that was now serving tractor-trailer trucks, we were back on 105. We were bleeding time and our stomachs began to voice their resentment, but we were back on the main road…

… a main road under construction in two spots. In both instances, traffic was knocked down to single lanes. However, at the first instance, we had to wait 20 minutes in line before continuing due to a possible shift change and/or a blossoming incompetence in full flower. That first stop was so bad, the driver in the car ahead of us, we were second in line, got out of the car and started yelling at the flag man. This led to an oncoming tractor-trailer honking his horn at the driver due to the tight squeeze between the car and the orange cones on the other side.

It was approaching 5pm by the time we got to Baddeck, the largest town we’d see for a while. Without knowing the food situation in Ingonish, we decided to find an eatery there. What we found was the Lynwood Inn and its restaurant. The food there was excellent and it was a welcome respite from the frustrations of the drive.

With our bellies satisfied, we continued northward to the Cabot Trail and were able to appreciate the beauty of Cape Breton Island. For you New Englanders who might read this, Cape Breton Island is a lot like Mount Desert Island in Maine, except that a lake 5-6 times the size of Lake Winnepesaukee is on it. It’s huge. Getting around on the island will take hours, but the scenery makes the experience well worth it.

After a hilly, twisty-turny drive along the Cabot Trail, we got to our cottage around 7pm or so. After settling in, we took a walk to the cliff that fronts the property and found the path that led down to the rocky beach underneath. We spent a really nice evening walking around the rocks at high tide and enjoying the sunset colors in the evening sky. It was a tough drive, but well worth it.

Day Four: Thursday, 21-Aug

We stayed in Ingonish for two nights, as per the plan, knowing that the drive to get there was going to be a long one. With the hiking trails closed, we spent the day driving halfway around the Cabot Trail and driving to Bay St. Lawrence at the northern tip of the island. We took the road all the way to a dead end at the town pier. With all the driving we’d done, driving more of the Cabot Trail was not in either of our desires. Instead, we had a nice lunch at Morrison’s Restaurant and a decent pizza later in the evening all while enjoying our rocky beach along the shore. The closed hiking trails definitely impacted the itinerary, but neither of us cared. It was just a nice day to chill. One bonus was the darkness of the night sky. Claire got to see the stars of the Milky Way for the first time in her life. Throw in a night-time soak in the outdoor hot tub and we were not far from heaven.

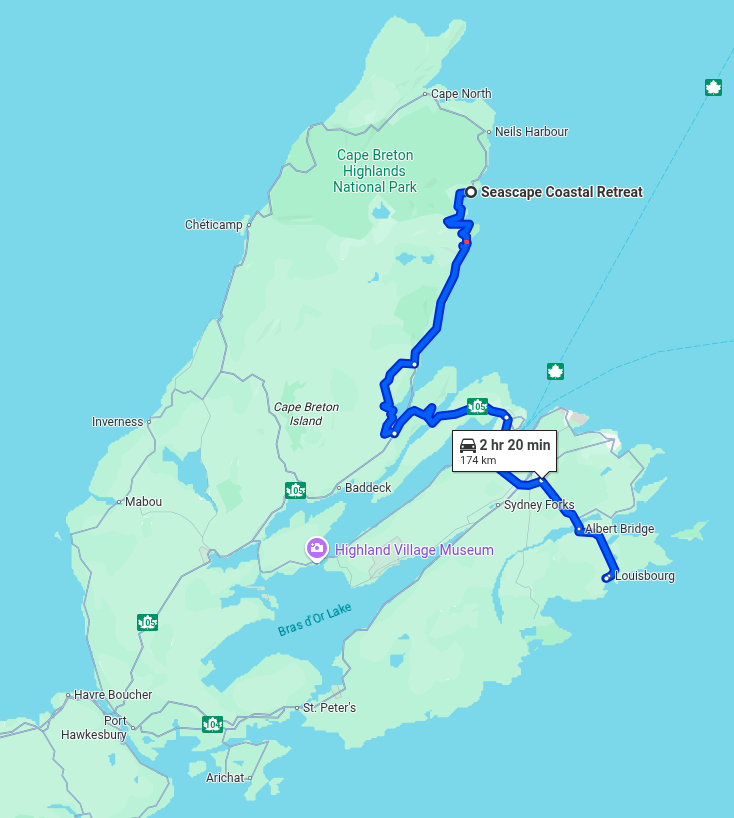

Day Five: Friday, 22-Aug

The crown jewel for the trip, and the primary reason I added Cape Breton Island to the itinerary was Fortress Louisbourg.

In 1755, Nova Scotia did not include Cape Breton Island. Île Royale, as it was known at the time, was still French territory. Defending this territory, as well as access to the Saint Lawrence, was the French naval fortress of Louisbourg.

Louisbourg was not impregnable. In 1745, a combined British and New England colonial force besieged it and captured it. During the negotiations at the end of the War of Austrian Succession, it was a major bargaining chip and was returned to France. England and the New Englanders were not happy.

With the outbreak of the French & Indian War, Louisbourg was once again a major target. The attack came in 1758 and, once again, the British and their colonial New England forces were victorious. This time, however, its fall signaled darker times.

Île Royale and Île Saint-John, modern-day Prince Edward Island, also French territory in 1758, contained many Acadian refugees from the numerous conflicts that beset Nova Scotia in 1755 and earlier. With a major French military influence based in Louisbourg, these Acadians were safe. Once the fortress fell, the Expulsion began on those islands in earnest. Not only did the fall of Louisbourg signal the eventual fall of Québec, but the eradication of Acadie, not only as a political and cultural entity but of its people as well, continued on its unpleasant course.

In 1961, the reconstruction of the ancient fortress was begun and it is currently a living history museum maintained by Parks Canada. It consists of the fortress keep and walls, entrance gates and supporting town. While most of it has been reconstructed, there are still some original stonework.

The drive to Louisbourg, a reasonable 2.5 hour one, retraced our path down the Cabot Trail. It was as pleasant a drive back as the way up. Once we reached infamous Route 105, we swung north towards Sydney and beyond, taking in the ever-scenic Bras d’Or Lakes.

After a bit of confusion as to how to enter the park, we drove to the Visitor Center and took a shuttle into the fortress. There are no parking spots near the fortress; all vistors are shuttled in.

Our second annoyance of the trip was once again due to hunger. We arrived in the fortress town at 12:30pm, lunch time. Unfortunately, it was lunch time for everyone else there, too. While there are options, such as cafes and quick take-out food, we opted for a sit-down experience in one of the two restaurants that provide that experience. Unfortunately, the “two” restaurants were really operating as one and they were at full capacity. While we were waiting in line, a tour group of 30 people showed up and cut the line. All told, we waited 75 minutes to get a seat and place our order. We didn’t leave the restaurant until 2pm.

Once we get past that experience, however, we immersed ourselves in the history of the place. Throughout, you will see actors dressed in period costume re-enacting scenes in both French and English. It was well worth the trip.

After taking in the fortress, we checked in to our B&B for the night, the Cranberry Cove Inn. While the website seems a bit dated, the accommodations were anything but. It was a very comfortable place to stay and our innkeeper provided us with very useful advice on where to make reservations for dinner.

Dinner was at The Bothy, a restaurant on the grounds of The North Star resort. As it was within walking distance of the B&B, we strolled down there as it first opened and was able to snag two spots at the small bar. The food was top-notch and the hospitality was as well. Live folk music from one of the locals added to the whole experience.

That night I went online to order the ferry tickets for the Digby to Saint John run we were to take on Monday, only to find the ferry booked up. The Yarmouth to Bar Harbor run was still open and I ordered those, but we would have to leave our inn early on Monday morning.

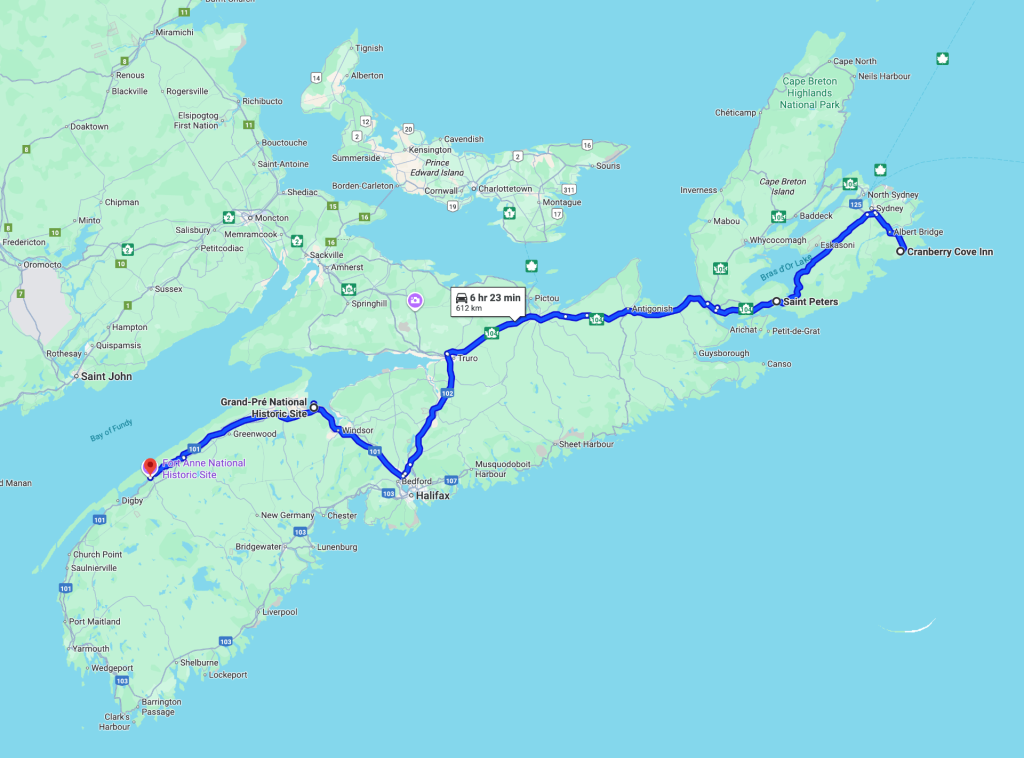

Day Six: Saturday, 23-Aug

After our best breakfast of the trip, a very well-seasoned eggs benedict, it was time to leave the island.

A look at the map doesn’t quite do the journey justice. It was just another long trek with only one lunch stop until we got to Grand-Pré National Historic Site northwest of Halifax. I will say that the views of Bras d’Or Lake, from whichever shore you are, are breathtaking, but once that’s done, it’s just drive, drive, drive.

Grand Pré was the historical lynchpin for me. This stop was the heart and soul of my pilgrimage and the raison d’être for the trip. I wasn’t conscious of it until Claire said as much in the shadow of that beautiful statue, as I was lost in thought considering my ancestor, Marie Modeste Doucet, and the fate of her family.

My existence, a piece of who I am, is the result of luck. Pierre Martin’s family fled inland to Québec in the wake of the Expulsions. The Bruns/Doucets wound up in Massachusetts. While not free from the discrimination that the French Neutrals faced in English lands, at least they were able to eke out a meagre living. Quite a few Acadians never got the chance, either dying at sea or in French hospitals or on-board ships in hostile harbors, holed up by an English colonial government and populace that simply didn’t want them. Marie Modeste and her family would spend 11 years in virtual captivity until James Murray, Governor of the Province of Quebec, issued a proclamation offering free land to new immigrants. In 1767, the Bruns/Doucets arrived in Québec after officially stating his desire to emigrate the year before.

Regaining my composure, we visited the memorial church near the statue, more a living monument than a place of worship. Inside we found religious statuary, typical for a Catholic Church, rolls of Acadian family names, scans of historical documents, paintings, murals and an ornate stained glass window. It was all very moving and somber and a very touching memorial.

After the visit to the church, we walked the grounds and found the Longfellow memorial, he the author of Evangeline, the epic poem which brought the Acadian experience out of the shadows of history. Further onward, we discovered signage explaining that an Acadian church once stood somewhere on these ground and that the graves of Acadian settlers were still in the soil in the surrounding fields, unmarked, unknown.

After a couple of hours here, it was time to head to our destination for the day, Annapolis Royal. Once known as Port-Royal, it was the capital of the Acadian colony. We would be spending two nights there.

The drive was uneventful, until we got to the Bridgetown area. In the distance, off to the east beyond a sheltering ridgeline, the rising smoke of the Long Lake Wildfire could be seen. While not in control, the rising smoke was not threatening, especially once we passed it.

We arrived at the Garrison House Inn around late afternoon. We were met by the wife of the innkeeping couple at the door and welcomed warmly. Thankfully, while their in-house restaurant to the public was closed due to staffing issues, as guests we were offered dinner. We accepted immediately and enjoyed a delicious meal with cocktails and wine.

It was still daylight when we finished our meal so we decided to take a walk around nearby Fort Anne and get a sense of the town. It was a good way to stretch our legs and reconcile the mix of English and Acadian influences on the area.

Our walk took us through the old fort’s cemetery across the earthen ramparts and down to the Annapolis River waterfront where we took in the sunset. As it got dark, we walked to the Annapolis Brewing Company’s bar and ordered a couple of beers. Mine was a chocolate stout and it was delicious.

Day Seven: Sunday, 24-Aug

In the morning, Claire and I returned to Fort Anne and entered the reconstructed officer’s quarters which served as the fort’s museum. Among all of the museums we had seen on this trip, it was among the best. The presentation of the complicated tragic history of the region was extremely well told, including the early Scottish settlement in the 1600s, a settlement which was removed when the territory was given back to France after yet another treaty after yet another war. One of the more interesting exhibits detailed the construction and destruction of the various forts which had been built in the town to defend it.

Following the museum tour, we took another walk around the ramparts and read the various historical markers sprinkled here and there. At one point, in spite of the handy wooden stairs, I decided to charge up the steep embankment of one of the typical fort ditches to the top of an earthen bunker. It was much easier to do without a row of bayonets waiting for me.

After this stop, we got into our car and drove to the other side of the Annapolis River along Granville Road to see the Port-Royal National Historic Site.

When I was a child growing up in Massachusetts, I visited quite a few colonial historic sites, such as Plymouth Plantation and Sturbridge Village. Here, finally, I was able to visit a colonial settlement of my own history.

The Port-Royal National Historic Site is a reconstruction of the initial encampment of the Acadians on Nova Scotia, the follow-up site after the winter at Saint Croix Island. Here, one of my ancestors, Louis Hébert, the first European apothecary in the New World, joined the camp a year after its construction.

“In March 1606, at the age of about 31, Hébert signed a contract with the explorer Pierre Dugua de Mons to serve a year in New France. His appointment as an apothecary brought him 100 livres, of which 50 were in cash.” The ship Le Jonas left La Rochelle on 23 May 1606 with about 50 pioneers and craftsmen, including Hébert, Poutrincourt, lieutenant-governor of Acadia, and Marc Lescarbot, lawyer and writer. They reached Port-Royal on 27 July. Hébert tended to sick colonists and indigenous people. The men did not waste time sowing wheat, rye, hemp and other grains. Marc Lescarbot wrote in his Histoire de la Nouvelle-France: “Poutrincourt … had a piece of land cultivated there to sow wheat and plant vines, as he did with the help of our apothecary, M. Louis Hebert, [a] man who, besides being experienced in his art, took great pleasure in tilling the soil.” After the harvest that fall, Poutrincourt and Samuel de Champlain explored the coast up to Cape Cod, in search of a second settlement. Hébert was part of the expedition.

Source: Wikitree

While the visit to this site would be very quick, the little fortified encampment was little more than a two-story wooden compound surrounding a small common square, I was finally able to visit a site about my history, my culture, albeit detached by time and circumstance.

After touring the little compound, Claire and I walked down to the river shoreline and took our seats in the ubiquitous red Adirondack chairs that one finds throughout Canadian national parks. It was there that I spied the infamous Île aux Chèvres (Goat Island) across the water. It was on or near this island, prominently mentioned in numerous accounts of the Expulsion, that the Acadians in the area were rounded up and boarded upon those nefarious ships. The chill I felt was palpable. The island is empty; no one lives there.

As we were leaving, I talked a bit with the workers there. I asked if any archaeology had been done on Île aux Chèvres for artifacts given the history and was told that nothing official had been done that they knew of. I think it might be a worthwhile endeavor.

After we left, we returned to our hotel and walked to the German bakery next door and had a delicious lunch there: for me a potato soup with a dunkel beer.

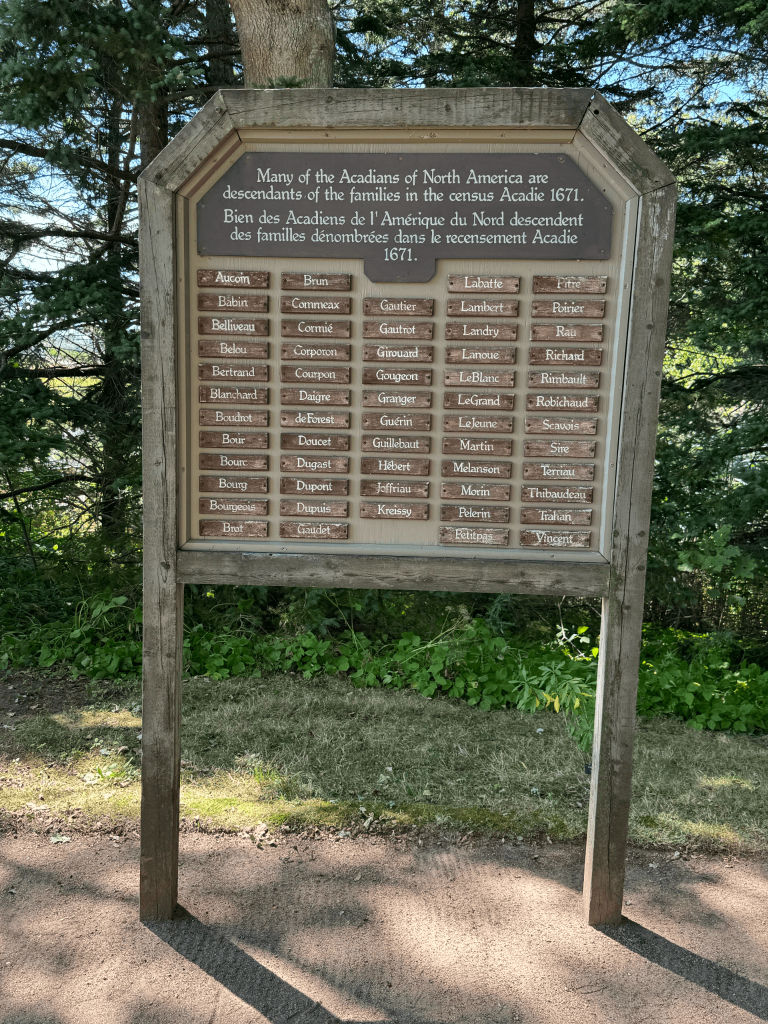

Following lunch, we walked to the Annapolis Royal Historic Gardens and spent the rest of the afternoon there, walking amid the various flora and lost in conversation. One of the areas of the garden featured an Acadian Cottage, an exhibit which needed quite a bit of restoration, truth be told. It was at this exhibit that I saw the sign, an image of which I had found online which began my journey through Acadian history.

That evening, Claire and I had dinner at The Whiskey Teller, an excellent eatery with an excellent whiskey and cocktail list. The food menu was a tad limited, but the quality was excellent.

After we returned to our room, and considering our early departure time and 1.5 hour drive, I decided to not close the trip with yet another long driving day. I made reservations for one night at the Holiday Inn Bar Harbor Resort and gave ourselves a bonus day.

Day Eight: Monday, 25-Aug

The morning drive was to the ferry was uneventful. However, the wildfire whose smoke we had seen on our drive in had doubled in size during the previous day, driven by the remnants of Hurricane Erin which was passing off-shore. During the previous day, both of our phones buzzed with evacuation alerts for the nearby towns. We were mildly concerned if this was going to impact our departure, but nothing of the sort happened.

The ferry ride was a welcome respite from the hours of driving had done. 3.5 hours of just sitting and napping. Thankfully, the weather and sea condition was not rough.

Our time in Bar Harbor was very laid back. Good food and drink in the hotel and a casual walk through the town and hotel grounds.

Day Nine: Tuesday, 26-Aug

All good things must come to an end. Following a good hotel breakfast, we jumped in the car and headed home via well-traveled familiar paths. The culture change was immediately felt, though. Gone was the serene, polite, well-ordered driving we had experienced over the past week. We were “back in the US, back in the US, back in the US of A”. (With apologies to The Beatles.) Quite a few ignorant folks like to claim that Canadians are just like Americans. They are not, and any reasonable comparison favors our northern cousins. It is no accident that I can count numerous friends across the once-friendly border. We are kin, if not in blood then in spirit. I’m happier traveling in Canada than I am elsewhere in the US and I certainly feel a lot safer.

Claire and I drove a lot, but we also saw a lot of history and nature and the delightful provinces of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. We will definitely return, but with a bit more focus.

The Realities of a Historical Tour

Time moves on and the past slips further away with each passing second. On military history tours, a lot of time is spent visiting monuments and cemeteries, the latter also being monuments of a sort. Battlefields get developed, new roads are built, life goes on and progresses. The same is true for genealogical or cultural tours, especially a tour focused on a culture and people which were systematically eradicated (or at least attempted).

My research into the demise of the Acadian Guérins influenced my initial itinerary for this trip, but given the amount of driving involved and the lack of meaningful attractions beyond the National Historic Sites, I skipped them entirely.

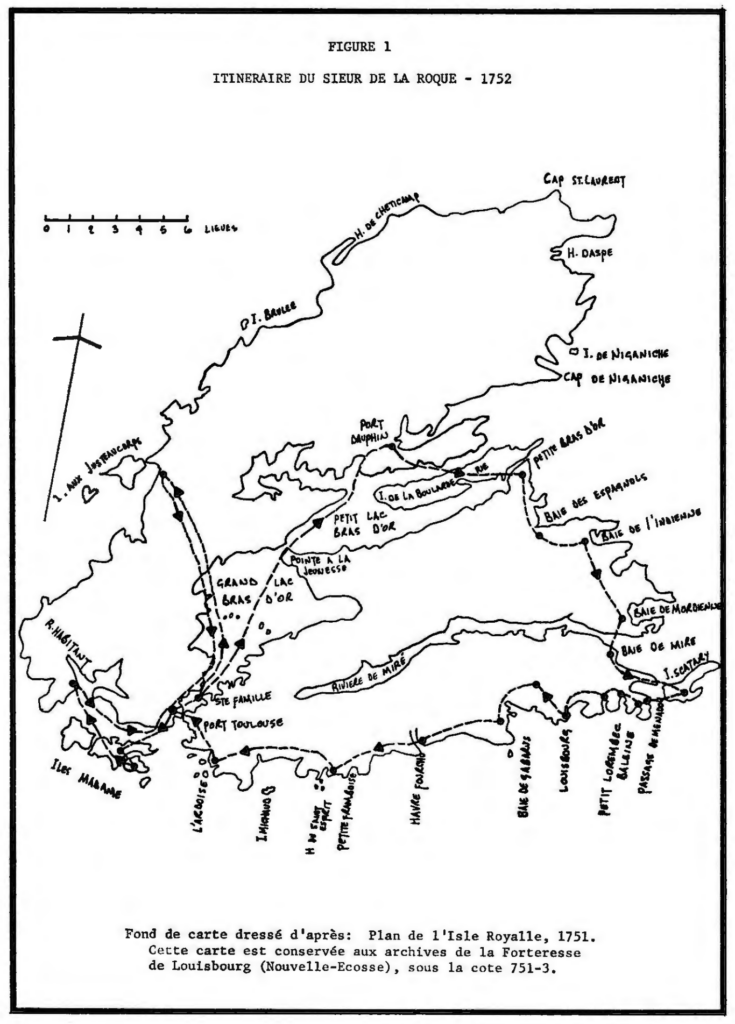

A large contingent of the Acadian Guérins, and their stories, wound up on Île Royale in the years prior to the Expulsions. Sieur de la Roque’s Census of 1752 showed multiple families, both Guérin and Guérin-wed, on Île Royale and Île Saint-Jean, all as new arrivals in the wake of the ongoing violence and cultural pressure in Nova Scotia proper.

I dropped two points of interest from the tour: Pointe à la Jeunesse and Baie de Mordienne. In 1752, Pointe à la Jeunesse was the home for two Guérin familes: Jean Baptiste Guérin (Marie Madeleine Bourg) and Dominique Guérin (Anne Leblanc). In Baie de Mordienne were four familes: Pierre Guérin (Marie Josephe Bourg), Claude Thériot (Marie Guérin), Pierre Thériot (Marguerite Guérin) and François Thériot (Françoise Guérin). Of course, these two locations are known by different names today: Grand Narrows and Port Morien respectively.

I removed these stops from the tour for two very good reasons: an already long amount of driving time and a distinct lack of anything to reference. The records are lost; the churches are gone; the cultivated property handed over to new settlers loyal to a different monarch. There’s simply nothing to see but land or property descended from another culture. So, I skipped all the stops related to the Acadian Guérins that I had planned.

However… the historical record is filled with interesting crumbs. When the expulsions of 1758 began, a servant of the Louisbourg Fortress named Pélagie Guérin was rounded up along with the others. She was shipped to France, having arrived on 01-Nov-1758 via the Antelope. She was most probably the daughter of Pierre Guérin and Marie Madeleine Bourg of Baie de Mordienne. Eight days after her arrival in France, the 21 year old woman left the port bound for the city of Rochefort, possibly to find the rest of her family who would have arrived via a different ship arriving in a different port. From here, she disappears from the historical record, as did most of her kin.

Je me souviens.