Evangeline: A Tale of Acadie (Prologue) – by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1847)

This is the forest primeval. The murmuring pines and the hemlocks,

Bearded with moss, and in garments green, indistinct in the twilight,

Stand like Druids of eld, with voices sad and prophetic,

Stand like harpers hoar, with beards that rest on their bosoms.

Loud from its rocky caverns, the deep-voiced neighboring ocean

Speaks, and in accents disconsolate answers the wail of the forest.

This is the forest primeval; but where are the hearts that beneath it

Leaped like the roe, when he hears in the woodland the voice of the huntsman?

Where is the thatch-roofed village, the home of Acadian farmers,—

Men whose lives glided on like rivers that water the woodlands,

Darkened by shadows of earth, but reflecting an image of heaven?

Waste are those pleasant farms, and the farmers forever departed!

Scattered like dust and leaves, when the mighty blasts of October

Seize them, and whirl them aloft, and sprinkle them far o’er the ocean.

Naught but tradition remains of the beautiful village of Grand-Pré.

Prologue: One Warp, One Weft

When I began writing this particular Guérin story, I had expected it to be a quick task. Look up some family lineage information, add some historical spice, format it somehow to make it interesting, and be done. The goal was to highlight and showcase another colonial Guérin line, one which wound up in a different colony on the North American continent. It was to be a side project, a simple addition to my own Guérin story.

Nothing about Acadian history remains a side project for long, nor should it. It is a long and complicated piece of history that quickly takes center stage once you are immersed in it. Acadian history is not merely one tale of tragedy, but an interwoven woeful saga of its own.

It is not my place, nor is it the purpose of this article, to rehash the entirety of this sordid drama. I can only pick one warp, one weft from the tapestry, somewhere nearer the edge perhaps, and bring it to light.

This is the story of François Guérin, but it is not merely the story of François Guérin. I am not directly related to François Guérin, but I am connected to him by heritage. By the time of the earliest Acadian census in 1671, he had already passed away, leaving only his widow and children to be reckoned. But now his story, and the story of his family, can be told.

François Guérin: Progenitor of His Line

According to Wikitree, François Guérin was born about 1635 in France, though this is merely an estimate. In his work “Histoire et Généalogie des Acadiens: 1600-1800”, Bona Arsenault states that François’ parents were Jérôme Guérin and Marie Blanchard, though the accuracy of the information in this book is a point of debate among historians.

In either 1658 or 1659, François married Anne Blanchard in Port Royal, Acadie, modern-day Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia. At the time of her marriage, Anne was approximately 14 years old. When François passed away in 1670 at the untimely age of 35, Anne became a widow at the age of 26, with five young children. The children were: Anne, Marie, Jérôme, Huguette and François. Of these, the youngest, François (it is believed) would pass away soon after the 1671 census. Of the remaining four children, Jérôme, being the only surviving son, would carry the family name forward.

Anne would soon remarry. 1672, she married Pierre Gaudet in Port Royal. Within this marriage, she would give birth to another 9 children. Anne Blanchard passed away at the approximate age of 69 in 1714 in the town of Beaubassin.

While François is counted among the founding members of the colony, he was one of the latecomers. At the time of his earliest recorded presence in Acadie, the registration of his marriage in 1658, the colony was already a tumultuous 54 years old.

A Quick & Dirty History of Acadie

According to Wikipedia, the colony of Acadie began when the French arrived in 1604 and claimed the Mi’kmaq lands for the King of France. Despite this intrusion into their native lands, the Mi’kmaq tolerated the French presence in exchange for favors and trade.

The first French settlement was established in 1604 on Saint Croix Island, off the coast of Maine, by Pierre Dugua de Mons, Sieur de Mons, Governor of Acadie under the authority of King Henri IV. The following year, the settlement was moved across the Bay of Fundy to Port Royal after a difficult winter on the island. In 1607, King Henri revoked Sieur de Mons’ royal fur monopoly. With the governor recalled back to France, the colonists returned with him and left Port Royal in the hands of their allies, the Mi’kmaq, led by the Grand Chief Membertou. When the former lieutenant governor, Jean de Biencourt de Poutrincourt et de Saint-Just, returned in 1610 as the new colonial governor, Port Royal was in the same condition as it had been three years ago.

The next few decades were not kind to the colony. The English, Scottish and Dutch, in turns, contested the French for possession of the colony and several battles were fought at Port Royal, Saint John, Cap de Sable (present-day Port La Tour), Jemseg, Castine and Baleine. During these battles, the towns were often raided and sacked and the population scattered with what livestock they could support off the farm. As if that wasn’t bad enough, from 1640 to 1645 an Acadian Civil War erupted between Governor Charles de Menou d’Aulnay de Charnisay stationed in Port Royal and Governor Charles de Saint-Étienne de la Tour stationed in Saint John (New Brunswick).

From the 1680s onward, six colonial wars were fought between New England and New France and their respective native allies. Following the successful British siege of Port Royal in 1710 during Queen Anne’s War, mainland Nova Scotia passed to British colonial government control via the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713. The rest of Acadia, consisting of Île Royale (Cape Breton Island), Île Saint-Jean (Prince Edward Island) and modern-day New Brunswick remained in French Acadian control.

The Oaths of Allegiance

With mainland Acadie coming under British control as Nova Scotia, the remaining Acadians were in a difficult spot. The French governors of Québec and Louisbourg wanted the remaining Acadians to exercise their rights under the Treaty of Utrecht to leave Nova Scotia for French-controlled lands. The British, on the other hand, were reluctant to see them leave. Without experienced residents, there is no colony. Without a colony, there is no food. Without food, there is no way for a military garrison to maintain the territory. The British needed the Acadians to stay in Nova Scotia. So wrote Samuel Vetch, in 1714:

“One hundred of the Acadians (who) were born upon this continent and are perfectly at home in the woods, (and) can march upon snowshoes and understand the use of birch canoes, are of more value and service than five times their number of raw men newly arrived from Europe. So their skill in the fishery, as well as the cultivating of the soil must make at once of Cape Breton the most powerful colony the French have in America, and to the greatest danger and damage to all the British colonies as well as the universal trade of Great Britain.”

“The removal of (the Acadians) and their cattle to Cape Breton would be a great addition to that new colony, so it would wholly ruin Nova Scotia unless supplied by a British colony, which could not be done in several years, so that the Acadians with their stocks of cattle remaining here is very much for the advantage of the Crown.”

Samuel Vetch, Governor of Nova Scotia, in letters to London, 1714

However, being of French heritage, the Acadian’s loyalties to the Crown would always be in question. The answer to this issue was the Oath of Allegiance: “I promise and swear on my Christian faith, that I will be faithful and maintain true allegiance to His Majesty King George, as long as I shall be in Acadia or Nova Scotia and that I shall be permitted to withdraw where so ever I shall think fit with all my moveable goods and effects when I shall think fit without any one…to hinder me.” It was similar to other such oaths that British subjects had to swear. However, the Acadians resisted. By 13-Jan-1716, only 36 Acadians had stepped forward to take this oath.

The primary sticking point for the Acadians was a fear that they would be obligated to take up arms against their brethren in any future conflict, if they swore the oath. It was a condition that the British were reluctant to allow, even though such conditions were made at other places and times. It took until 1739 for Governor Philips to make this condition official. The oath signed by the Acadians read:

“Je Promets et Jure Sincerement en Foi de Chretien que Je serai entierement Fidele, et Obeirai Vraiment Sa Majeste Le Roy George le Second, qui je reconnais pour Le Souverain Seigneur de L’Acadie ou Nouvelle Ecosse. Ainsi Dieu me Soit en Aide.” (I promise and swear sincerely as a Christian that I will be entirely faithful, and truly obey His Majesty King George II, who I acknowledge as Supreme Lord of Acadia or Nova Scotia. So help me God.)”

The Acadian Oath of Allegiance

Note that the condition against taking up arms is not included in this version. Governor Philips did not send that piece of the oath back to London. Instead, two French priests, Fathers Charles de la Goudalie and Noel Alexandre De Noinville, certified that “His Excellency Richard Phillips…has promised to the inhabitants of (the Minas Basin) and other rivers dependent thereon, that he exempts them from bearing arms and fighting in wars against the French and the Indians, and that the said inhabitants have only accepted allegiance and promised never to take up arms in the event of war against the Kingdom of England and its Government.”

At this point, the Acadians were referred to in both Halifax and London as “French Neutrals”.

The Establishment of Halifax and Growing Opposition

While the swearing of the oath brought some peace and prosperity to the region, it did not last long. Growing Acadian families made it clear that the British were never going to outnumber them in the colony. The establishment of a new settlement and fortress at Halifax made it clear that the British intended to grow their influence, culture and religion in the region. Successive governors also took a more aggressive stance against the Acadians and demanded an unconditional swearing of the Oath of Allegiance. The Acadians resisted, but, for the most part, kept true to their original oaths.

Unfortunately, more conflict between the French and English came to the region, and with each one animosity built upon animosity. British regulars and militia battled and sieged while some French Acadians and native Mi’kmaq raided British settlements. Warfare raged from the major coastal centers of Annapolis Royal to the French fortress at Louisbourg and to such far-off inland locales as Norridgewock, Maine. While most Acadians kept true to the original oaths, the others who took part in such guerilla conflicts as Father Le Loutre’s War, called the loyalty of the entire Acadian population into question in the minds of their British masters.

The French & Indian War in Acadie

When the final French & Indian War erupted in 1755, Acadie became a primary strategic British target. The view was that the pathway to Québec, the heart of French colonial presence in North America, was via the Saint Lawrence River and that that pathway was blocked by the French fortress at Louisbourg. However, given all of the raids and irregular warfare practiced by the Acadians and Mi’kmaq against British settlements in mainland Nova Scotia during Father Le Loutre’s War (1749-1755), an area still primarily populated by Acadians and Mi’kmaq, the British, at the outbreak of this new war, demanded that the Acadians sign a final unconditional oath of allegiance to Britain, an oath which included the relinquishment of their firearms. When the Acadians attempted to negotiate with the British authorities and eventually refused to sign such an oath, the British resorted to drastic and tragic measures to ensure their control over Nova Scotia and the security of vital supply lines for a future siege of Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island.

La Grand Dérangement

La Grand Dérangement, aka The Great Upheaval or The Expulsion of the Acadians, is the name given to the forced deportation of thousands of French Acadians from the colony of Acadie during the French & Indian War. The deportations, while constant, occurred in two phases separated by the fall of the fortress of Louisbourg in 1758.

According to Wikipedia, the expulsion began after the fall of Fort Beauséjour in 1755 with the Bay of Fundy Campaign. In this first wave, between six and seven thousand Acadians were deported from Nova Scotia to the British American colonies. After the successful siege of Louisbourg in 1758, a second wave consisting of the St. John River Campaign, Petitcodiac River Campaign, Gulf of St. Lawrence Campaign and the Île Saint-Jean Campaign began. In this second wave, thousands more were forcefully expelled from their homelands, though this time to France.

In all, of the 14,100 Acadians living in the region at the beginning of the French & Indian War, 11,500 were expelled, of which at least 5,000 (~43%) died of disease, starvation or by shipwreck during the voyage. During this expulsion, men, women and children were forcibly removed from their homes and land, land they had farmed for over a century. Their houses were burned and their land given to settlers loyal to Britain, mostly immigrants from New England and Scotland.

The event is largely regarded as a crime against humanity, though contemporary use of the term “genocide” is debated by scholars. A census of 1764 indicates that 2,600 Acadians remained in the colony having eluded capture.

Source: Wikipedia: Expulsion of the Acadians

On 11-Jul-1764, the British government passed an order-in-council to permit Acadians to return to British territories in small isolated groups, provided that they take an unqualified oath of allegiance. Some hundreds did return to the colony.

The Myth of Louisiana

It is widely believed today that the Acadians were deported from their colonial homelands directly to Louisiana. As noted above, these refugees were either sent to France or scattered throughout England’s or France’s colonial possessions. It was a subsequent grant by Spain, then owner of current-day Louisiana, that enticed these refugees to take the risk of ocean-going travel to settle in a new land. This grant was made in 1785, some 20+ years after the end of the French & Indian War. They did so at their own cost and risk.

The Historical Record of François Guérin

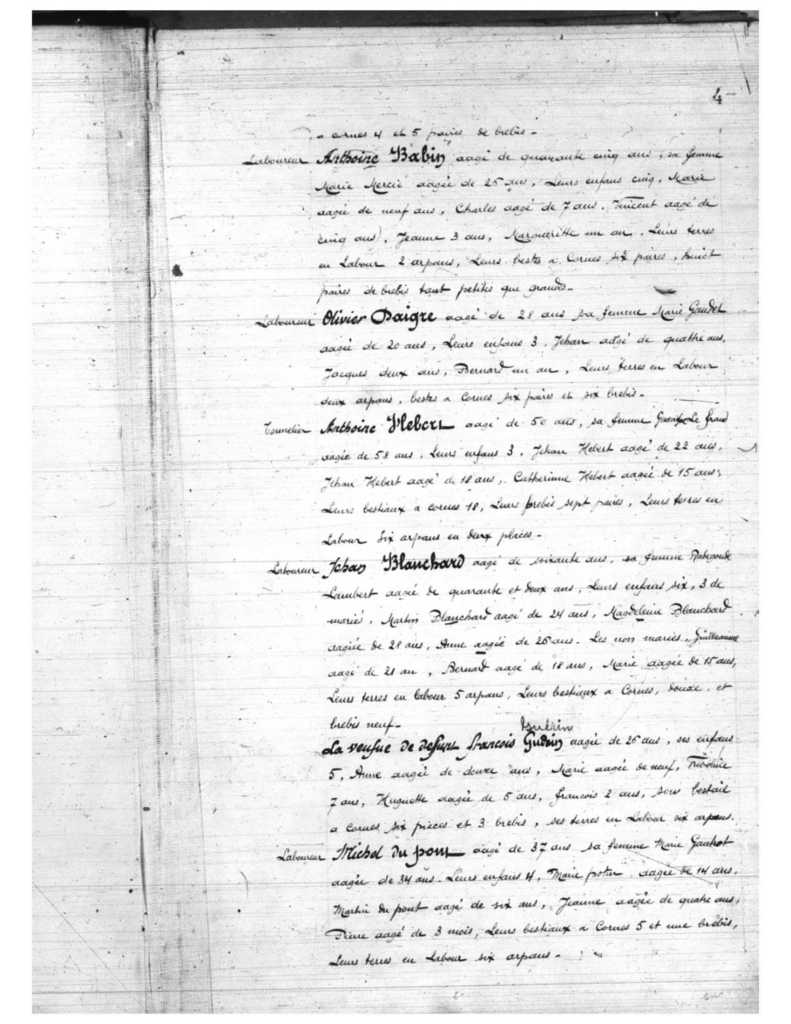

Due to La Grand Dérangement, many of the church records were destroyed. The date given earlier for François’ marriage is an assumption based on the ages of Anne and their children, as is his birth year. The earliest existing record of François is in the 1671 Acadian Census in the count of his widow, Anne Blanchard (translated):

Widow of François GUDCIN (GUERIN), aged 26 years; her 5 children: Anne aged 12 years; Marie aged 9 years; Frivoline 7 years; Huguette aged 5 years; Francois 2 years; cattle 6, sheep 3, 6 arpents of cultivated land.

Source: 1671 Acadian Census

This census entry is somewhat corroborated by the testimony of Claude Marc Pitre, the husband of Isabelle Guérin, François’ and Anne’s granddaughter. In the following excerpt from “The Acadians in France, Vol. 2, Belle Isle en Mer Registers, La Rochette Papers” (compiled, translated and edited by Milton P. Rieder, Jr. and Norma Gaudet Rieder):

On February 28, 1767 appeared Claude Pitre living in the village of Arpens de Triboutons, parish of Sauzon. Who in the presence of Jean Baptiste LeBlanc, Simon Pierre Daigre, Joseph Babin and Armand Granger witnesses, all Acadians living on this island, declared that he was born at Port Royal on May 13, 1700 of Marc Pitre and Jeanne Brun of the said place; Marc Pitre born of Jean Pitre originally Flemish and of Marie Pincelet of Paris. Jeanne Lebrun (Brun) daughter of Sebastien Lebrun and Henriette Bourg and Sebastien Lebrun issued of Vincent Lebrun who came from France with his wife Marie Brault and both died at Port Royal. The said Claude Pitre married at Cobeguit, parish of Saint Pierre and Saint Paul June 12, 1724 to Elisabeth Guerin born at the said Cobeguit September 29, 1704 of Jerome Guerin and Elisabeth Aucoin. Jerome Guerin was the issue of another Jerome Guerin who came from France married to Marie Blanchard. The said Jerome Guerin died at Port Royal and Marie Blanchard at Beaubassin. Elisabeth Aucoin was born at Beaubassin of Martin Aucoin who came from France, married at Port Royal to Marie Gaudet and both died at the said place. Of the first marriage of Claude Pitre with Elizabeth Guerin was born at Cobeguit, in the said parish of Saint Pierre and Saint Paul, December 17, 1726, a boy named Joseph Pitre who married at the said place Anne Bourg daughter of Ambroise Bourg and Elisabeth Melancon of Isle Saint Jean in North America, Diocese of Quebec; the said Elizabeth Guerin died at sea with the rest of her family in 1758 on an English ship which was shipwrecked in transporting a party of Acadian families from the said Isle Saint Jean to Europe.

Claude Pitre married a second time in England at Liverpool May 9, 1760 to Magdeleine Darois born at Mines, parish of Saint Charles, in 1715 of Jerome Darois who came from Paris and married at Port Royal to Marie Gareau and died at the Riviere de Petkoudiak in the Bay of Beaubassin. The said Marie Gareau died in Virginia, she was the daughter of Dominique Gareau who came from France, married Anne Gaudet at Port Royal and both of them died at the said place. The said Magdeleine Darois married in 1749 to Alexis Trahan born at Pigiguit, parish of l’Assomption, in 1727 of Alexandre Trahan of Port Royal and of Marguerite LeJeune. Alexandre Trahan issued of another Alexandre Trahan of Port Royal who was married at the said place to Marie Pellerin and the said Alexandre Trahan descended from Guillaume Trahan who came from France and of Magdeleine Brun, both of them died at Port Royal. Marguerite LeJeune born at Port Royal in 1698 of Pierre LeJeune and Marie Thibodault of Port Royal. The said Pierre LeJeune issued of another Pierre LeJeune who came from France, married at Port Royal and died there.

Of the marriage of the said Magdeleine Darois and Alexis Trahan, deceased at Liverpool in England in the month of July 1756, was born at Pigiguit, parish of l’Assomption the 10th of August 1752, Paul Trahan the only son of this marriage is living at the village of Arpens de Triboutons, parish of Sauzon with his mother and his step-father Claude Pitre.

Such is the declaration of the said Claude Pitre who having it read to him stated that the contents were right and that he could not sign the accounting in accordance with the ordinance. Completed and drawn up under the signatures of the witnesses named as being present, of Messire Joseph Benoist parish priest of Sauzon, of Messire Jean Louis Le Loutre missionary priest and of us clerk, at the said Sauzon March 12 of the said year.

Signed: Joseph Babin, Jean Baptiste LeBlanc, Simon Pr. Daigre, Armand Granger, J.L. Le Loutre ptre. miss., Jh. Benoist cure de Sauzon and Thebaud commis.

Source: “The Acadians in France, Vol. 2, Belle Isle en Mer Registers, La Rochette Papers”

This deposition took place in the French town of Arpens de Triboutons on 28-Feb-1767. It was a sworn statement to prove to the French that he was of French stock and should be allowed to stay in the country following his expulsion from Acadie.

The story contains excellent, necessary genealogic details. Though Claude errs in stating that Isabelle’s grandfather was named Jérôme, instead of François, he gives the correct lineage of his late wife. Isabelle was a daughter of Jérôme Guérin and Isabelle (Élisabeth) Aucoin. As he was reciting his late wife’s family tree from memory, we can forgive the error.

Jérôme Guérin: Namesake

Who was Jérôme Guérin? The existing records are contradictory. In the 1671 census, he is not explicitly listed by name. It is accepted by Acadian historians that Jérôme is the ¨Frivoline¨ listed in the census. Meanwhile, François the younger in the census disappears afterward and seems to have died in infancy. This is the generally held opinion. However, I believe that François was actually François Jérôme Guérin and that it was Frivoline who passed away. If so, then François and Anne would have been following French-Canadian custom and had named their first-born son after his father.

The 1698 Acadian Census does not help us answer this question, though we can see why Frivoline was chosen to be Jérôme. The four surviving children of François Guérin and Anne Blanchard are all married by this time and are registered accordingly:

- Port Royal

- Charles Doucet 40 & Huguette Guerin (wife) 27; Claude 13, Charles 10, Jean 8, François 6, Madeleine 4, Germain 1/2

- Jérôme Guérin 33 & Élisabeth Aucoin (wife) 18

- Beaubassin

- Pierre Arsenau 48 & Marie Guérin (wife) 36; Abraham 20, Charles 9, Jacques 7, François 4, Anne 1

- Laurent Chastillon 42 & Anne Guérin (wife) 35; Marie 18, Guillaume 16, Charles 10, Marie Josephe 8, Marie Madeleine 4, François 1½

Comparing these ages against the 1671 census shows errors in one or the other. In the 1671 census, Anne was the oldest. Here, she is younger than Marie. Huguette should be 32, not 27, especially considering that the 1671 census took place 27 years before this one. Only Marie’s ages match. If Jérôme were Frivoline, then his age would also match. However, there are errors that off by 4-5 years, if the 1671 census is considered to be the accurate one. On the other hand, this census puts Jérôme in between his older sisters and Huguette, which would match Frivoline’s position in the 1671 census.

Later censuses add more confusion. In the 1700 Acadian census, Jérôme is missing, probably on his way to Cobeguit, which wasn’t covered in that census. In the 1701 Acadian census, of the three men living in Cobeguit with their families, one of them is Giraud Guérin. In the 1703 Acadian census, we find Giraut Guérin living there with his wife and three daughters, all unnamed. In the 1707 Acadian census, we finally have definitive proof that it is Jérôme living in Cobequid. An entry for that town shows a Girault Guérin living with his wife, Isabelle Aucoin, and their three daughters. An entry in the 1714 Acadian census, the last known or surviving census until the 1750s, shows Jérôme living with his wife, 1 son and six daughters.

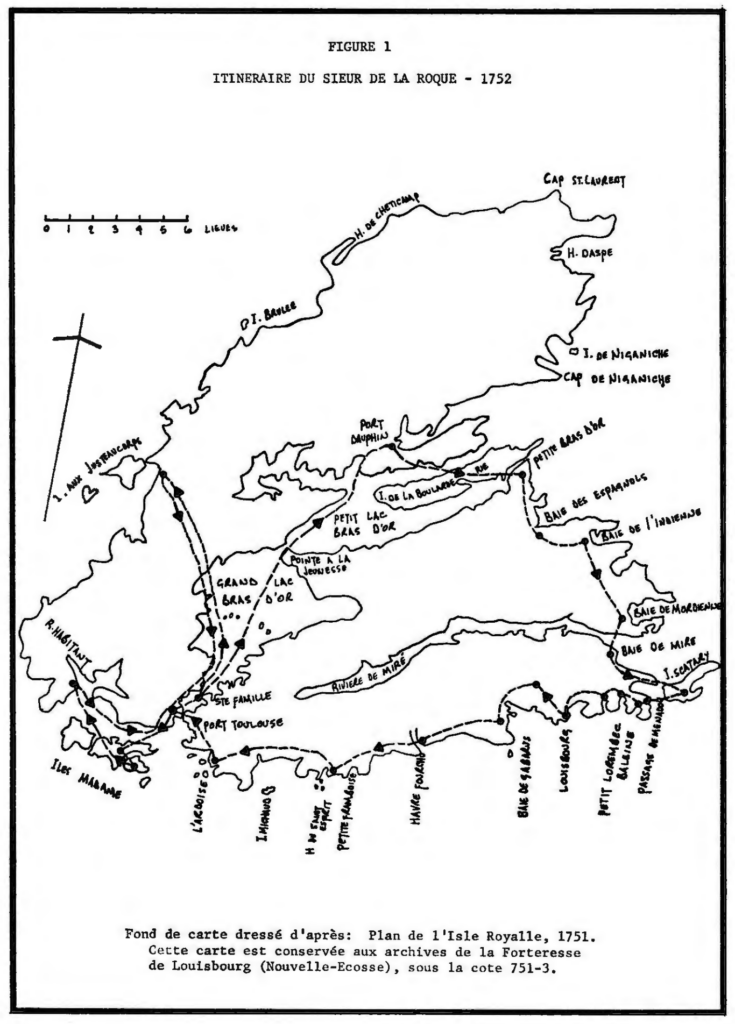

Regardless of the various discrepancies and suppositions, based on the 1698 census, Jerome Guérin married Isabelle Aucoin in Cobeguit, Acadie around 1698. Together, the couple would have 11 children who survived infancy: Judith, Marie, Isabelle, Marguerite, Françoise, Pierre, Henriette, Jean Baptiste, François, Dominique and Charles. Little is known regarding the passing of Jérôme Guérin. No records survive. In the accounting of the 1752 census of Îsle Royale and Îsle Saint-Jean by the Sieur de la Roque, his wife, Isabelle Aucoin, is living with her son, Charles, at Rivière du Ouest on Îsle Saint-Jean, so it is safe to say that he had passed by then. As to Isabelle Aucoin’s fate, nothing is definitively known after that census.

With five boys, the seed stock available to carry on the Guérin name was promising. The incessant conflicts in the region, and the subsequent expulsions, would prove otherwise.

1755: The Expulsions Begin

When La Grand Dérangement begins in 1755 in the area around Fort Beauséjour, the Guérin boys and their families are not immediately affected. By 1752, all five had married and settled off the mainland. Most of the Guérin girls, all married, also migrated off the mainland. Within the records of the 1752 census of Îsle Royale and Îsle Saint-Jean by the Sieur de la Rocque, we find the following information:

- Îsle Royale (Cape Breton Island)

- General Census of the Settlers at the Pointe à La Jeunesse

- Jean Baptiste Guérin (33) & Marie Madeleine Bourg (32): Jean Pierre (2), unnamed (2 mos) [ in country: within 1 year ]

- Dominique Guérin (31) & Anne Leblanc (25): Anne Josephe (5), Nastay (3), Marguerite (1) [ in country: within 1 year ]

- General Census of the Settlers in the Baie de Mordienne

- Pierre Guérin (40) & Marie Josephe Bourg (39): Pierre (17), Pélagie (15), Isidore (13), Louis (10), Luce (8), Gertrude (6), Marie Josephe (3) [ in country: 18 months ]

- Claude Thériot (56) & Marie Guérin (53): Madeleine (25), Théotiste (23), Mathieu (22), Marguerite (20), Françoise (18), Anne (14), Romain (12), Hélène (9), Ignace (6) [ in country: almost 2 years ]

- Pierre Thériot (58) & Marguerite Guérin (45): Jean Baptiste (24), Marguerite (20), Marie Madeleine (19), Anne (17), Anselme (14), Françoise (12), Fabien (10), Brisset (8), Geneviève (4) [ in country: almost 2 years ]

- François Thériot & Françoise Guérin (42): Marie (22), Marguerite (20), Pierre (18), Madeleine (16), Isabelle (14), Perpétue (12), Théodose (10), Cyrille (8), Gertrude (6), Anne (4), Joseph (2) [ in country: 1 year]

- General Census of the Settlers at the Pointe à La Jeunesse

- Îsle Saint-Jean (Prince Edward Island)

- Census of Rivière du Ouest

- Charles Guérin (27) & Marguerite Henri (27): Terile (5), Marin (2), Élisabeth Aucoin (74, mother of Charles) [ in country: 2 years ]

- Census of the Settlers of the Grande Ascension

- François Guérin (34) & Geneviève Mius (32): Marguerite Geneviève (5), Marie Rose (3) [ in country: 2 years ]

- Census of the Settlers of Anse à Pinnet

- Olivier Boudrot (41) & Henriette Guérin (40): Marguerite Josephe (10), Madeleine Josephe (8), Anne Marie (7), Basile (6), Mathurin (3)

- Census of Rivière du Ouest

As can be seen from the summary above, nine of the Guérin clan had arrived on Îsle Royale and Îsle Saint-Jean within 2 years of the census. In fact, there seems to have been a rush to find some place for them as the census also includes notes regarding the state of the land being settled and the conditions of settlement.

(regarding the settlers at Pointe à La Jeunesse) When all the settlers landed on their arrival from la Cadie in August last, they owned between them the number of 188 oxen or cows, 42 calves, 173 sheep or ewes, 181 pigs and 17 horses. A comparison with the recapitulation will easily show how many of these have perished from want of hay on which to feed. The settlers had not even water to give them within reach, and now all ask to leave so fully do they realize that they cannot live there.

(regarding the settlement of Claude Thériot) The land on which they are settled is on the west point of the Lake de Mordienne on the lands lying south of the bay. The quality of the land does not seem to be at all suitable for the cultivation of wheat. It is reddish, sandy and very light. There is not more than a foot of soil to work, and under that is found a bed of rock.

So what happened to cause this large-scale emigration from Cobequid, where most of the Guérin clan originated, to land which seems to be barely habitable?

It should be noted that Cobequid, though not as far away from the English fort at Annapolis Royal as were the French communities at Chignecto, was, nonetheless, in those days of slow travel, one of the more remote Acadian centres; and, as such, the Acadians of Cobequid were more independent than most. So, too, the Cobequid Acadians were close to an Indian mission located where the Stewiacke meets the Shubenacadie; and which had been run, for many years, by Le Loutre. The close proximity of Le Loutre and his native friends (the sworn allies of the French crown) meant that the Acadians of Cobequid dare not ever get too friendly with the English. We see, for example during January, 1750, at Cobequid, on the church steps, in the presence of their priests, Le Loutre, with Indians at his back, threatened death to any Acadian who should travel to trade with the English.

Source: “The Lion and the Lily” by Peter Landry

This Le Loutre is none other than Father Jean-Louis La Loutre, the namesake of Father La Loutre’s War, which ran from 1749-1755, right up against the final French & Indian War. In the episode described in the narrative, we see a level of French-led animosity against even their own people.

Whereas the Sieur de la Rocque’s 1752 census accounts for 9 of Jérôme and Isabelle’s children, Judith, wife of Claude Bourg, and Isabelle, wife of Claude Marc Pitre, are unaccounted for. At this time, they are still in mainland Nova Scotia: Judith and her family in Annapolis Royal and Isabelle and her family in Cobequid. Unfortunately, the events of 1755 were soon to catch up to them.

The Deportation of Claude Marc Pitre

According to “The Pitre Trail from Acadia” by Wendy Pitre Roostan, Claude Marc Pitre was born on 13-May-1700 in Port Royal, Acadie. As Port Royal was attacked in 1704 during one of the many conflicts, it seems that Claude’s parents and family moved up the coast to be further away from British control. On 12-Jun-1724, he married Isabelle Guérin, daughter of Jérôme Guérin and Isabelle Aucoin, at Cobeguit. However, King George’s War (1744-1748) caught up to them:

In 1744, when hostilities resumed between the French and the English, the Acadians were accused of supporting the French. The council at Port Royal had ordered an investigation of the allegations and the two representatives who came from Cobequit in December of 1744 were Claude Pitre and Pierre Theriot — probably Claude Marc and his wife’s brother-in-law. No action seems to have been taken at this time.

Source: Wikipedia: King George’s War

In August, 1755 after the fall of Fort Beauséjour at the beginning of the French & Indian War, the expulsions were begun in earnest. Cobeguit was one of the early targets. This is corroborated by the diary of Jeremiah Bancroft, an ensign in Captain Phineas Osgood’s Company, one of eleven companies comprising the First Battalion of the Regiment of Governor William Shirley of Massachusetts.

From “Operations at Fort Beauséjour and Grand-Pré in 1755: A Soldier’s Diary” by Jonathan Fowler and Earle Lockerby, the following excerpts were transcribed from his diary:

Ye 6 (of August) A party of 100 men commanded by Capt Lewis Marcht for Cobegit Satterday 30th (of August) ... 3 Sloops arrived hear from Boston The 10th (of September) Neer 300 men of the french put on board the transports

While the men of Cobeguit were rounded up and taken away, the women and children of these families trekked overland to Tatamagouche on the northern coast and made their way to Île Saint-Jean (Prince Edward Island) by boat. When the British returned to Cobeguit to get them as well, no one was there. This is how Claude Marc Pitre became separated from his wife and family as explained in the testimony above.

When Isabelle Guérin and her children escaped to Île Saint-Jean, she was reuniting with her extended family. For the time being, Isabelle and her children, and children’s families, were safe, but her husband had been caught up in the initial net at Cobeguit.

To Virginia and England

After Claude Marc Pitre and the other men of Cobeguit were picked up by the British, they were taken to Grand Pré and embarked aboard transports to be distributed throughout the British colonies.

The embarkation began on October 8, 1755 and continued until the 28th of October. In order to hasten the undertaking, the ships used were overloaded and to make room for even more, the Acadians were forced to leave practically all of their goods on shore, where they were found still lying on the shore by the English settlers who came six years later. The crowding of the ships in excess of their complement made conditions aboard the vessels dangerous to health and prevented the Acadians from carrying much of their household goods with them. In an account of the embarkation, manuscripts show that the authorities considered the Acadians being “shipped” with no more concern than they would have in the shipping of cattle. The lack of, or disregard for the ships’ manifests, shows that they didn’t appear to be concerned with names, only numbers. “I have made some blunder by the loss of the principal list of those who embarked – but the number of souls that embarked on board of these transports were 2921 – how many embarked afterwards I know not” – (“ACADIA” -Edouard Richard Vol. 2, Chapter XXXI, pp. 120-121) – (Naomi E.S. Griffiths – “THE ACADIAN DEPORTATION: Deliberate Perfidy or Cruel Necessity” – p. 143 [quoting a manuscript account of Brown compiled in 1760’s]) Because of the lack of manifests, or passenger lists, there is no record of those Acadians who died at sea. Only, that they mysteriously disappeared from any record or census following the expulsion.

Source: “The Ships of the Acadian Expulsion”

Six of these ships formed a convoy that departed Grand Pré at Pointes des Boudro on 27-Oct-1755 and headed for the colony of Virginia. They were: Endeavor (ex-Encherée), Industry, Mary, Neptune, Prosperous and the Sarah and Molly.

From the same source, we get a sense of what happened to the convoy through the telling of the Endeavor’s travels :

The ship ENDEAVOR, 83 tons, John Stone Captain arrived at Grand Pre (Pointe des Boudro) from Boston on August 30 and embarked on 19 October The Endeavor departed 27 October, 1755 from Pointe des Boudro (Grand Pre) with 166 exiles for Virginia and arrived in Virginia on 15-30 November, 1755, The Endeavor was one of the six transports that took shelter from a fierce winter storm in the Boston Harbour on November 5, 1755. While at Boston to seek shelter for a number of days, the vessel was inspected and an undisclosed number of Acadians were removed to reduce the number aboard to 2 persons per ton. The delay in the voyage when they were in the Boston Harbour for a few days further depleted their supplies which were low since the beginning of the voyage. So, fresh water and minimal supplies and assistance was given to the passengers on board the Endeavor by the Massachusetts Bay authorities and the vessels sailed southward. Edouard Richard mentions a “Corvette Endeavor”, 83 tons with a Captain Stone as master being used to transport 166 exiles. According to copies of accounts transmitted by Charles Apthorp & Thomas Hancock, of Boston Mercantile Company Apthorp and Hancock , to Governor Lawrence published on pages p. 285 – 293 of SELECTIONS FROM PUBLIC DOCUMENTS OF THE PROVINCE OF NOVA SCOTIA, Published by resolution of the House of Assembly on March 15, 1865 in 1869 – the Sloop Endeavor (also known as Encheree), John Stone master was chartered from Boston Mercantile Co. Apthorp and Hancock from hence to Minas & Virginia to carry off French inhabitants from 21 August to 11 December. The monthly charter fee for the Endeavor was 3 months 21 days 44 pounds 54 pr month , pounds sterling – plus 60 s p. month for hire of a pilot , plus provisions. The amount of provisions for the transports were included in the sailing orders issued by Lawrence was to be 5 pounds of flour and one pound of pork (or 1 lb of beef 2 lbs bread and 5 lbs of flour) for (each) 7 days for each person so embarked. According to the publication “The Acadian Exile in St. Malo”, the governor of Virginia refused to accept the Acadians that were allotted to Virginia, and the 1,500 Acadians sent to Virginia on October 25, 1755 were in Virginia were not allowed to disembark and more of them died aboard the crowded ships during the 4 months that the ships were anchored in the Williamsburg harbor. They were then transported to England and placed in concentration camps in the port cities of their arrival, where they languished until after the Treaty of Paris, in 1763, when they were released and repatriated to the maritime ports of Normandy and Brittany.

Source: “The Ships of the Acadian Expulsion”

This was how Claude Marc Pitre wound up in Liverpool, England. The governor of Virginia, due to the defeat of Braddock’s army in western Virginia and Pennsylvania, did not want a large number of French civilians in the colony, whether as prisoners or not. The Virginia frontier was becoming an active theater of war and taking care of detainees would have placed a burden on the colony’s efforts to prosecute the war. So the approximately 1500 Acadians were detained on board their vessels for four months in wintry, abysmal conditions, dying as they did so, until the convoy set sail for England in the spring.

The Family of Claude Bourg & Judith Guérin

The other Guérin descendant of Jérôme Guérin and Isabelle Aucoin who was still on the mainland in 1755 was Judith Guérin, wife of Claude Bourg. Judith was the eldest of the Guérin clan; by 1755 she would have been about 57 years old.

According to Judith’s profile at Wikitree, Claude and Judith had eleven children. Of these, Isabelle passed away at the age of 17 in 1737. Four of the remaining children accounted for were married by 1755:

- Marguerite Bourg married Jean Baptiste Babineau on 30-Jan-1748 in Annapolis Royal

- Two children were born: Jean Baptiste (b. 11-Jul-1749) & Joseph (b. 04-Jun-1752)

- Joseph Bourg married Marie Josephe Doucet on 03-Feb-1750 in Annapolis Royal

- Claude Bourg married Marie Guilbeau on 15-Nov-1751 in Annapolis Royal

- Anne Bourg married Charles Melançon on 14-May-1753 in Annapolis Royal

The remaining children have no surviving historical record apart from their baptismal registrations. Claude Bourg passed away on 05-Jun-1751, four years before the expulsions began.

The rounding up of Acadian families in Annapolis Royal was slow to develop as it was furthest from the heart of the British operations in the Chignecto region. However, by 08-Dec-1755, most of the Acadian families of Annapolis Royal had been rounded up for embarkation aboard the transports of a seven-ship convoy. One of the ships of the convoy, was the Pembroke.

The Pembroke Incident

Pembroke was a 139-ton snow under the command of a Captain Milton. On 08-Dec-1755, she set sail from Île aux Chèvres (Goat Island), off the coast of Annapolis Royal, as part of the 7-ship convoy carrying ~1660 Acadians in their holds. While each ship was headed to different ports of call, the Pembroke’s destination was North Carolina and she was carrying 232 Acadian detainees on board. Unfortunately for the English captors, the crew of the Pembroke numbered only eight. When bad weather separated the Pembroke from the other ships of the convoy, somewhere off the coast of New York, the detainees were able to overpower the ship’s crew and take it over. Once under their control, the Acadians turned the ship around and sailed back toward Acadie.

Luckily, even though they were in British-controlled waters, the Pembroke did not encounter any other ships until they reached the mouth of the Saint John River in Acadie (modern-day New Brunswick) on 08-Jan-1756. As it was winter, the Acadians had set up a camp near the mouth of the river and had anchored the Pembroke near the shore, using it to store what supplies were on board.

A month later, on 09-Feb-1756, an English ship, duplicitously flying the French flag, arrived in the vicinity. They stated that they were from Louisbourg and were looking for a pilot to help them navigate the local waters. One of the Acadians went to the ship to be their pilot and was promptly taken prisoner. The ship then flew the English ensign and opened fire on the Pembroke. The Acadians, seeing the commotion, removed their supplies from the ship and set it on fire to prevent it from falling back into the hands of the British. From there, the Acadians left their camp and traveled inland to the town of Sainte-Anne-de-Pays-Bas, modern-day Fredrickton. Unfortunately, the arrival of over 200 people stretched the town’s meager, late-winter provisions to the breaking point.

Regarding the encounter between the English ship and the Pembroke near the mouth of the Saint John River, Governor Charles Lawrence of Halifax wrote a letter to Massachusetts Governor William Shirley on 18-Feb-1756:

I lately sent a party of Rangers in a schooner to St. John’s River. As the men were clothed like French soldiers and the schooner under French colours, I had hopes by such a deceit, not only to discover what it was doing there but to bring off some of the St. John’s Indians. The Officer found there an English ship, one of our Transports that sailed from Annapolis Royal with French inhabitants aboard bound for the continent, but the inhabitants had risen upon the master and crew and carried the ship into that harbour, our people would have brought her off but by an accident they discovered themselves too soon, upon which the French set fire to the ship. They have brought back with them one French man, who says there have been no Indians there for some time … he informs me also that there is a French officer and about 20 men twenty-three miles up the river at place called St. Ann’s.

With winter still gripping the small town of Sainte-Anne-de-Pays-Bas amid dwindling provisions, the French resistance leader, Charles Deschamps de Boishébert et de Raffetot sent most of the families toward Nouvelle-France via the Saint John River by canoe. Quite a few of these refugee families made it to the safety of Nouvelle-France, but not without cost.

The Guérin Connection to the Pembroke Incident

Like the other expulsion transports, the Pembroke did not have a passenger manifest. The Acadians were like cattle to them. That said, several historians have attempted to recreate the passenger list for the Pembroke, given its unique history.

Anne Bourg and her husband, Charles Melançon, were among those who fought back against their oppressors and regained their freedom. Anne Bourg was the youngest child of Claude Bourg and Judith Guérin. According to the same source, their first child, Charles, was born around December, 1755, meaning that Anne gave birth to the child shortly before being rounded up for deportation or while on board the Pembroke. As the child was not mentioned as part of the counting of the passengers, it is probable that he was born on board or shortly after arriving at the Saint John River. Unfortunately, due to the perils of the long trek to Nouvelle-France, Charles died 01-Sep-1757 in Québec City from a smallpox epidemic that was ravaging the city at the time. Charles the elder would pass away himself on 31-Dec-1757 at Saint-Charles-de-Bellechasse outside of Québec City. In spite of all this, Anne would give birth to Jean Baptiste Melançon some time in 1756 to 1757 and would remarry in 1758.

Source: “La Societé Historique Acadienne: Les Cahiers, Vol. 35, Nos. 1 & 2, Janvier-Juin 2004”

While “Les Cahier” does not list them as probable passengers on the Pembroke, it is possible that Claude Bourg (Anne’s brother) and his family may have have been on the ship as well. According to “Les réfugiés et miliciens acadiens en Nouvelle-France” by André-Carl Vachon, Claude Bourg and his family made their way to Nouvelle-France by ship from Miramichi on 03-Aug-1757 and arrived in Québec City fifteen days later. Given the timeline and the location of Miramichi in relation to Annapolis Royal and Sainte-Anne-de-Pays-Bas, it is possible that Claude was on the Pembroke as well. Regardless of the exact circumstances, Claude, his wife Marie Guilbeau, and their daughter, Marie Josephe, escaped the deportation and were able to make it to Nouvelle-France. Additionally, some time in 1756 during their flight, Marie also gave birth to daughter, Anne. Unfortunately, Anne passed away in Québec City on 25-Jun-1758. Marie Josephe, the couple’s other daughter, has disappeared from the historical record; presumably she passed away some time prior to their arrival in Nouvelle-France. The couple would go on to have five other children in Nouvelle-France, the first of whom would be named Marie Josephe.

The Remainder of the Bourg Clan: Lost to History

The fates of Judith Guérin and the rest of her children, and her children’s families, are lost to history. No further record of their lives past 1755 survives. Presumably, none survived the expulsion.

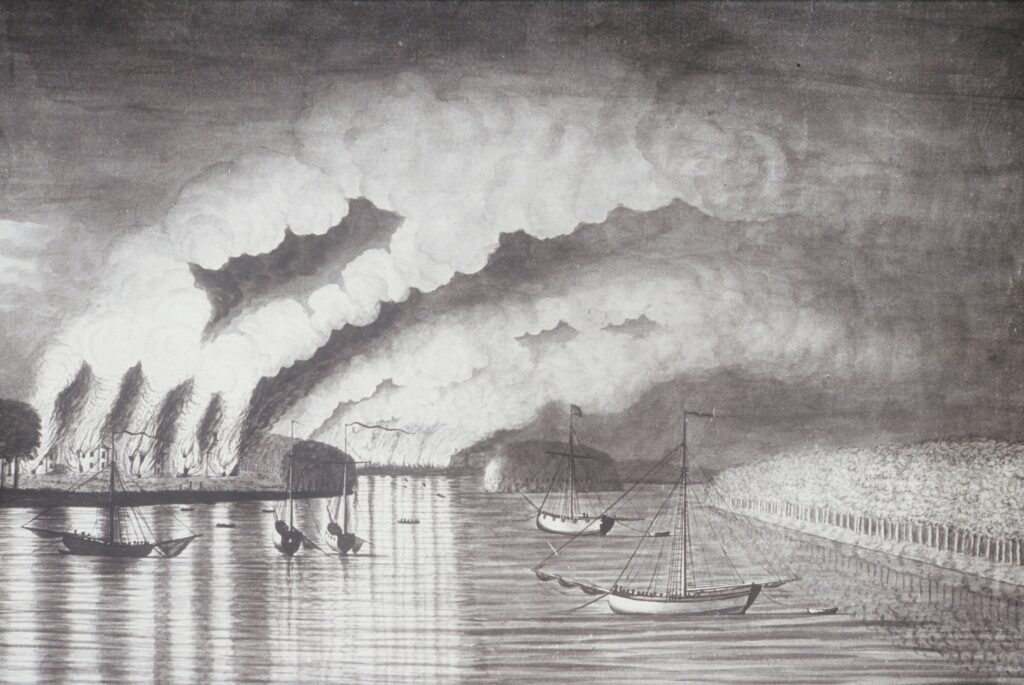

1758: Annus Horribilis

For three years, the nine remaining children of Jérôme Guérin and Isabelle Aucoin, and their families, would be safe on the islands of Îsle Royale and Îsle Saint-Jean. When the fortress of Louisbourg fell in 1758, however, access to Îsle Royale and Îsle Saint-Jean, as well as the Saint Lawrence River, were now open to the British navy and the predations of the British and Colonial infantry. It didn’t take long for the British to exert their baleful influence.

By late November, 1758, roughly three months after the fall of Louisbourg, approximately 2200 Acadians from these islands had been rounded up and deported in two convoys.

The first convoy departed Île Royale in early September 1758 and consisted of the following ships: Antelope, Britannia, Duc Guillaume, Reine d’Espagne, Duke of Cumberland, Richmond, Britannia (2nd of that name) and Mary. Of these, four arrived at Saint-Malo, France, three at La Rochelle and one at Brest.

The second convoy was a 12-ship convoy which departed Chédabouctou Bay on 25-Nov-1758. The transport ships were: Duke William, John Samuel, Mathias, Neptune, Patience, Restoration, Ruby, Supply, Tamerlane, Violet and Yarmouth. Of these, two, Duke William and Violet, would sink in a winter storm off the southwestern coast of England and one, Ruby, would be caught in the same storm and dashed on the rocks and sunk at Pico in the Portuguese Azores. The survivors of the latter incident were taken to England and France aboard the Portuguese schooner Santa Catarina and the English ship, Bird, arriving at Le Havre on 15-Feb-1759. Only four Acadians survived the sinking of the Duke William and none survived the sinking of the Violet.

The conditions on the ships were terrible with many Acadians dying from disease and exposure during the crossing. Several more died in hospital after arriving in France. All told, approximately 1500 Acadians died due to shipwreck or disease during the crossing.

As with the deportations of 1755, passenger manifests were not maintained. However, an accounting was done in France to record the immigrants. Even so, it is nearly impossible to determine the exact fates of those who perished and on which ship they did so. I can only present here a summary based on the research work of others, most notably the lists compiled by Louis Xavier Perez from documents conserved by the Archives de la Marine à Brest. Research to construct the passenger manifests of these ships continues to this day.

The Family of Claude Marc Pitre & Isabelle Guérin

As detailed above, Isabelle and her family escaped Cobequid in 1755 and moved to Îsle Saint-Jean after her husband, Claude Marc Pitre, was collected by British soldiers along with the other men of the village. Or, to be precise, she and the children living with her escaped Cobequid. Claude and Isabelle’s older children had been married by 1755 and had their own adventures.

Joseph Pitre & Family

Claude and Isabelle’s eldest son, Joseph, was married by 1755. Around 1752, he married Anne Bourg and the couple had had one child by 1755, Anne Pitre, born around 1753 and baptized in Cobequid. The couple’s second child, Firmin, was born and baptized on 17-Aug-1755 at Port LaJoye, on Îsle Saint-Jean. This is mere days from the fall of Fort Beauséjour and the sortie of the soldiers to round up the men of Cobequid. It is probable that Joseph, Anne and their children had moved to Île Saint-Jean prior to the events of 1755. In fact, the baptismal record of Firmin states that the couple were living in Rivière du Ouest and not in Port LaJoie proper or in l’Acadie.

A scan of the 1752 census by Sieur de la Rocque of the inhabitants of Rivière du Ouest show quite a few Pitres, Bourgs and a couple of Guérins. It is not improbable that Joseph, reacting to the instability brought about by Father La Loutre’s War, or the impending start of yet another French & Indian war, moved his young family to Îsle Saint-Jean prior to 1755.

When the British came to Île Saint-Jean in 1758, it seems that Joseph and his family once again escaped the net that scooped up the others. There is a record of a “Joseph Pitre, Anne Bourck, 4 enfants” as living on Île Saint-Jean in 1763. This Joseph is probably Claude and Isabelle’s eldest child. (See the Wikitree entry for Joseph Pitre for more information.) This line of Pitres seems to have survived the second expulsion by escaping it entirely.

Anne Josephe Pitre & Family

On 01-Jun 1757, Anne Josephe Pitre married Ambroise Bourg, in Louisbourg. Ambroise was the cousin of Joseph Pitre’s wife and first cousin (once removed) of Claude Bourg, Judith Guérin’s husband. When the fortress fell the next year, the couple were taken by the British and deported in the second expulsion. On 16-Dec-1759, Anne gave birth to daughter Louise in Cherbourg, France. Unfortunately, the infant girl perished on the following day, followed by her mother four days after that, ending that part of the Guérin/Pitre lineage.

Ambroise Bourg would remarry; on 11-Jul-1763, he married another Acadian deportee, Marie Modeste Moulaison, in Cherbourg. On 12-Aug-1785 Ambroise, Modeste and their 9 children departed from France on the ship La Ville d’Archangel, which arrived in Louisiana on 03-Dec-1785.

Isabelle and her Two Boys

Claude Marc and Isabelle had three other children: Alexandre, Jean Baptiste and Catherine Josephe. Catherine passed away on 27-Aug-1756 at Port Lajoie on Île Saint-Jean, prior to the deportations. Isabelle and her two boys presumably passed away on one of the ships that succumbed to the storms that hit the convoy. As there were no passenger manifests, it is impossible to state which ship they were on, though it is certain that Isabelle died at sea aboard either the Duke William or the Violet along with her sons.

Summary: The Line of Isabelle Guérin

The line of Isabelle Guérin is survived only by the line of her eldest child, Joseph Pitre, due to his ability to evade the collection and forced expulsion of his brethren. According to Wikitree, Joseph and Anne would have seven children and 25 grandchildren and their descendants would range from Prince Edward Island to Nova Scotia to Massachusetts. One such descendant was Ethel Adelaide Conway of Rollo Bay, Prince Edward Island, a great-great-great-great-granddaughter of Isabelle and Claude Marc. Ethel was born on 19-Nov-1907 and passed away in 2001 at the age of 93. Her maiden name was Peters, a phonetic Anglicization of Pitre. Her family line had remained on Prince Edward Island since the hostile times of 1763.

Three Families: The Guérin Sisters and the Thériot Brothers

From 1726 to 1729, three Guérin sisters married three Thériot brothers. They were:

- Claude Thériot and Marie Guérin (m. 1726)

- Pierre Thériot and Marguerite Guérin (m. 1727)

- François Thériot and Françoise Guérin (m. 1729)

The brothers were the sons of Germain Thériot and Anne Pellerin, an Acadian family who also wound up on Île Saint-Jean.

In 1752, the three couples were living on Île Royale at Baie de Mordienne:

Claude Teriau, ploughman, native of la Cadie, aged 56 years. Married to Marie Guérin, native of the same place, aged 53 years. They have nine children, three sons and six daughters: Mathieu, aged 22 years; Romain aged 12 years; Ignace aged 6 years; Madeleine, aged 25 years; Téotite, aged 23 years; Margueritte, aged 20 years; Françoise, aged 18 years; Anne, aged 14 years; Eleine, aged 9 years.

They own in live stock: one ox, five cows, two pigs, one horse and twelve fowls.

On Michaelmas day next they will have been two years in the colony, and they have been given rations for that time.

…

Pierre Teriau, ploughman, native of la Cadie, aged 58 years. Married to Margueritte Guérin, native of the same place, aged 45 years. They have nine children, four sons and five daughters: Jean Baptiste, aged 24 years; Ancelme, aged 14 years; Fabien, aged 10 years; Brisset, aged 8 years; Margueritte, aged 20 years; Marie Madeleine, aged 19 years; Anne, aged 17 years; Françoise, aged 12 years; Geneviève, aged 4 years; all natives of la Cadie.

In live stock, they own: two oxen, four cows, one horse and six fowls.

…

François Teriau, ploughman, native of la Cadie, aged 49 years. Married to Françoise Guérin, native of the same place, aged 42 years. They have eleven children, four sons and seven daughters: Pierre, aged 18 years; Theodose, aged 10 years; Cirille, aged 8 years; Joseph, aged 2 years; Marie, aged 22 years; Margueritte, aged 20 years; Madeleine, aged 16 years; Isabelle, aged 14 years; Perpétue, aged 12 years; Gertrude, aged 6 years; Anne, aged 4 years.

They will have been in the colony one year at the beginning of Auguest next, and have been given rations for nine months.

Live stock: seven oxen, nine cows, eleven sheep, one mare, three pigs and four fowls.

They have not made an inch of clearing where they are, not having had time through change from one place to another. They are at Fausse Baye since the end of the month of September. They cut the hay for feeding their animals on the banks of the Barachois de Mordienne and of Fausse Bay. The quality of the land is similar to that at the Baie de Mordienne.

Source: Report concerning Canadian Archives for the year 1905, Volume II (Tour of the Inspection Made by the Sieur de la Roque)

The three couples, like the other members of the extended Guérin family and the families of their spouses are newly arrived on the islands. The census for Baie de Mordienne lists other Teriau(sic) families as well, including their eldest son, Joseph, who was married to Marie Rose Gaudet. The family of Pierre Guérin and Marie Josephe Bourg (see below) were also living at Baie de Mordienne.

In 1758, they were all rounded up for expulsion by the British.

The Family of Claude Thériot and Marie Guérin

Online information related to the fate of Claude Thériot and his family are scarce. It is known that Marie Guérin and two of her children, Romain and Ignace, passed away within days of each other at the Hôpital des Orphelins in Rochefort. It is also known that three of the seven ships of the initial deportation convoy from Louisbourg that set sail in September 1758 went to La Rochelle and not Saint-Malo, their intended destination. As Rochefort is in the general area of La Rochelle, it is possible that Claude and his family had embarked on either the Duke of Cumberland, Richmond or Britannia and arrived in the Rochefort area in late October.

Théotiste Thériot also passed away at the Hôpital des Orphelins in Rochefort in late October. She was married by the time of the deportations. On 17-Nov-1752, she married Joseph Boutin in Louisbourg. Nothing more is known of his fate or the fate of their children.

The Family of Pierre Thériot and Marguerite Guérin

Like most of the Thériot families, Pierre and his wife, Marguerite Guérin, were loaded aboard the Duc Guillaume with five of their children: Françoise, Geneviève, Brice, Anselme and Anne. Pierre, Anselme and Anne died at sea. Marguerite and her son, Brice, died in the hospital at Saint-Malo within a month of their arrival. Only Françoise and Geneviève survived.

Eldest son, Joseph, who was already married by the 1752 census, was also loaded aboard the Duc Guillaume with his wife and their three daughters: Rose, Anne and Josephe. Of the five members of the family, Anne and Josephe died at sea while Marie Rose, Joseph’s wife, died in hospital days after their arrival. Only Joseph and his daughter, Rose, survived the ordeal, though she, too, would pass some time in 1762. On 07-Feb-1764, Joseph would marry Jeanne Françoise Guilbert in Saint-Malo, a native-born French woman.

A second elder son, Jean Baptiste Thériot, married Marie Josephe Cyr on 27-Sep-1761 in Roxbury, Massachusetts Bay Colony. He was deported there, but it is not known when. Over the next few years, he and his family travelled between Saint-Malo and Saint-Pierre et Miquelon, the latter being invaded during the American Revolutionary War and its French inhabitants deported. He and his wife would have six children, most of whom would marry and have children.

An elder daugher, Marie Madeleine Thériot, married Jean Blouin on 03-Feb-1755 in Louisbourg. Her family is listed in the 1770 list of refugees in La Rochelle having been deported from Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon. Perhaps, she and her brother had been living there prior to the deportations of 1758.

Nothing is known regarding the fate of siblings Marguerite and Fabien Thériot.

The Family of François Thériot and Françoise Guérin

By the time of the deportations, François’ family had grown beyond what was reported in the 1752 censu. Three more children were born: Adrien, Modeste and Jean Baptiste; the former two were twins.

The crossing aboard the Duc Guillaume was not kind to François and his family. Twelve of their children travelled with them; two were old enough to have their own families. François himself died at sea along with five of his children: Joseph, Isabelle, Perpétue, Modeste and Jean Baptiste. His wife, Françoise, and four of their children, Théodore, Gertrude, Anne and Marguerite Josephe, were in hospital over the course of the next month. All four survived hospitalization.

The Thériots would settle in France and marry until 1785 when several would board the Spanish ship La Ville d’Archangel and migrate to Louisiana, including 75-year-old Françoise.

The Family of Pierre Guérin and Marie Josephe Bourg

In 1752, the family of Pierre Guérin has been counted among the inhabitants of Baie de Mordienne on Îsle Royale among the families of three of his sisters:

Pierre Guérin, ploughman, native of la Cadie, aged 40 years. Married to Marie Joseph Bourg, native of the same place, aged 39 years. They have seven children, three sons and four daughters: Pierre, aged 17 years; Isidor, aged 13 years; Louis, aged 10 years; Pélagie, aged 15 years; Luce, aged 8 years; Gertrude, aged 6 years; Marie Joseph, aged 3 years.

They have been in the colony 18 months and have been granted rations for 21 months. They own live stock: two cows, two pigs, six sheep, and three fowls.

Source: Report concerning Canadian Archives for the year 1905, Volume II (Tour of the Inspection Made by the Sieur de la Roque)

It seems that both Pierre and his wife, Marie Josephe, passed away before the deporatations, though details are scarce. The children, however, were deported along with their aunts’ families.

According to the debarkation lists at Saint-Malo, the children of Pierre Guérin travelled on the Duc Guillaume with the Thériot families. Of the six children recorded, three died at sea and one died in hospital soon after arriving. The surviving children were Pierre and Louis, the latter of whom was also hospitalized upon arrival in port.

There is some confusion regarding the registration at Saint-Malo and the census of 1752. Among those on the census who are not registered at Saint-Malo are Isidor, Pélagie and Luce. An Agricole is listed as a sister of Pierre and Louis in the Saint-Malo registration.

However, a Pélagie Guérin, registered as a servant at Louisbourg, is listed among the passengers of the Antelope. She is also listed as having departed for Rochefort on 09-Nov, eight days after her arrival. No age is given for her, though the name was not a common one. Perhaps she left for Rochefort having had news of family members heading for that town. Nothing more is known of her fate.

Not much information is given for the fates of Pierre and Louis Guérin. According to some sources, both became seamen and neither married nor had issue.

The Family of Olivier Boudrot and Henriette Guérin

In 1752, the family of Olivier Goudrot were living on Îsle Saint-Jean at Ance à Pinnet:

Olivier Boudrot, ploughman, native of l’Acadie, aged 41 years, he has been in the country two years. Married to Henriette Guérin, native of l’Acadie, aged 40 years. They have two sons and three daughters: Bazille Boudrot, aged 6 years; Mathurin, aged 3 years; Margueritte Josephe, aged 10 years; Magdelaine Josephe, aged 8 years; Anne Marie, aged 7 years.

And in stock two oxen, four cows, two calves, one bull, one heifer, five pigs and twenty-three fowls or chickens.

The land on which they are settled is situated at the farther end of Ance à Pinet to the south of the said ance. It was given to them verbally by Monsieur de Bonnaventure. On it they have made a clearing for a garden only.

Source: Report concerning Canadian Archives for the year 1905, Volume II (Tour of the Inspection Made by the Sieur de la Roque)

The family of Olivier Boudrot and Henriette Guérin were aboard one of the “Five Ships” which arrived in Saint-Malo on 23-Jan-1759. Of the six members of the family, only Olivier and Henriette survived the crossing. The four youngest children died at sea during the journey. Daughter, Magdeleine Josephe, was not traveling with her family and did survive the crossing, arriving at Saint-Malo in January, 1759 with the other deportees. While Henriette did survive the crossing, she died in hospital two months later on 21-Mar-1759 in Saint-Malo.

The Family of Jean Baptiste Guérin and Marie Magdeleine Bourg

In 1752, Jean Baptiste Guérin and his family were living at Pointe à La Jeunesse on Île Royale. The conditions of their situation were recorded as follows:

Jean Bte. Guérin, ploughman, native of la Cadie, aged 33 years. Married to Marie Madeleine Bourg, native of la Cadie, aged 32 years. The have two sons: Jean Pierre, aged 2 years; the last, aged 2 months, is not named.

In live stock, they own one cow and two pigs.

Source: Report concerning Canadian Archives for the year 1905, Volume II (Tour of the Inspection Made by the Sieur de la Roque)

Before the La Grande Dérangement, two more children would be born: Marie Madeleine, born in 1754, and Xavier, born in 1756.

Jean Baptiste and his family were among those who arrived at Saint-Malo aboard one of the “Five Ships”. Unfortunately, the two youngest children, Marie Madeleine and Xavier, would die at sea during the crossing to France.

After their arrival in France, Jean Baptiste and his family settled in Saint-Suliac. Two more children would be born to the couple: Joseph in 1760 and Ambroise in 1762. Jean Baptiste would pass away in Saint-Suliac in the late 1770s. His son, Jérôme, married fellow Acadian Marie Pitre in Saint-Suliac in the late 1770s and this couple would be one of the nine Acadian Guérins who migrated to Louisiana in the 1780s. According to one source, Ambroise passed away in 1779.

The Family of François Guérin and Geneviève Mius

In 1752, François Guérin and his family were living on Îsle Saint-Jean. In the census of Îsle Royale and Îsle Saint-Jean by the Sieur de la Roque, they are listed as living among the inhabitants of Grande Ascension, near the current-day town of Millview on Prince Edward Island. The family were registered thusly:

Francois Guerin, ploughman, native of l’Acadie, aged 34 years, he has been two years on the Island. Married to Genevieve Mius, native of l’Acadie, aged 32 years. They have two daughters: Margueritte Genneviève Guerin, aged 5 years; Marie Roze, aged 3 years.

And in stock they have four pigs and twelve fowls.

The land on which they are settled, is situated on the west bank of the east river of the Grande Ascension, it was given to them verbally by Monsieur de Bonnaventure.

They have made a clearing on it for the sowing of four bushels of wheat in the coming spring.

Source: Report concerning Canadian Archives for the year 1905, Volume II (Tour of the Inspection Made by the Sieur de la Roque)

Not mentioned in the report is their third daughter, Anne Modeste Guérin, baptized on 02-Nov-1751. Either she passed away prior to the census of 1752 or was not born yet at the time of its registration.

Regardless, the entire family drowned at sea when the Duke William, the ship they were loaded aboard, foundered in winter storms during the Atlantic crossing to France.

The Family of Dominique Guérin and Anne Leblanc

Around 1752, the family of Dominique Guérin, like his brother Jean Baptiste, were eking out a living at Pointe à La Jeunesse on Île Royale. They were recorded in the census thusly, next to the entry for Jean Baptiste:

Dominique Guérin, ploughman, native of la Cadie, aged 31 years. Married to Anne Le Blanc, native of la Cadie, aged 25 years. They have three daughters: Anne Joseph, aged 5 years; Nastay, aged 3 years; Margueritte, aged 1 year.

They have two pigs.

Source: Report concerning Canadian Archives for the year 1905, Volume II (Tour of the Inspection Made by the Sieur de la Roque)

Three more children were born to the couple prior to their forced deportation: Joseph, Françoise and Marie. While the exact ship is not known, they were aboard one of the “Five Ships” which arrived in Saint-Malo. Only six of the eight family members survived the crossing. Anastasie, aged 10 years, and Françoise, aged three years, died at sea. Of the remaining four children, two more died in hospital soon after their arrival: Anne Joseph, aged 12 years, and Marie, aged 3 months.

Over the next 10+ years, the family settled first at Ploubalay, then Trigavou in the Saint-Malo area. Four more children would be born: Isabelle in 1760, Françoise in 1763, Anastasie in 1766 and Brigide in 1769. In 1767, Anastasie would pass away.

Over the following 10+ more years, the family, like other displaced Acadians would migrate to France’s interior to try their hand at farming. For Dominique Guérin and his family, that would be the Poitou region. Eventually, they, and other Acadians, would again migrate to the Nantes area. Here, Anne Le Blanc would pass away on 10-May-1782.

In March, 1776, son Joseph married Agnès Pitre in Saint-Similien parish in northwest Nantes. Two daughters were born to them at Nantes: Marie-Joséphine in St.-Similien Parish in January 1777 and Françoise in St.-Jacques Parish in April 1784.

In the early 1780s, the Spanish government offered displaced Acadians some land in Louisiana. Dominique and his family took up the offer and departed aboard three of the Seven Ships which made up the convoy of Acadian settlers to Louisiana. Dominique, sailing aboard La Bergère, passed away at sea.

Joseph Guérin and his family also made the crossing to Louisiana aboard the La Bergère. No record of their daughters is found. They had another daughter, Agnès, born at Lafourche in Louisiana in September 1787, but they had no sons, ending this part of the Guérin line with him.

As to the daughters of Dominique Guérin, two of his unmarried daughters made the journey: Isabelle, aged 25, and Brigide, aged 15. Isabelle would marry Jean Pierre Landry, son of fellow Acadians Proper Landry and Isabelle Pitre at Lafourche in February 1786, but would die shortly thereafter. Her husband married in 1790.

Brigide would marry François Jean Thibodeaux, son of Acadians Blaise Thibodeaux and Catherine Daigle at Lafourche in July 1796. Brigide passed away in Assumption Parish in April 1830.

The Family of Charles Guérin and Marguerite Henry

In 1752, Charles Guérin and his family were living in the area of Rivière du Ouest on Îsle Saint-Jean. They were recorded in the census as follows:

Charles Guerin, ploughman, native of l’Acadie, aged 27 years, has been two years in the country. Married to Marguerite Henry, native of l’Acadie, aged 27 years. They have one son and one daughter: Marin, aged 2 years; Terille, aged 5 years. Elizabeth Aucoin, mother of the said Charles Guerin, native of l’Acadie, aged 74 years.

In live stock they have two oxen, one wether, one ewe, two sows, one pig and fourteen fowls or chickens.

The land on which they are settled is situated as in the preceding case, as was given to them under similar conditions. They have made a clearing for the sowing of about four bushels of wheat.

Source: Report concerning Canadian Archives for the year 1905, Volume II (Tour of the Inspection Made by the Sieur de la Roque)

Two more children were both to Charles and Marguerite in Acadia prior to the Expulsion: Marguerite Joseph in 1753 and Alexis in 1758.

As with the other Guérins, Charles and his family arrived at Saint-Malo aboard one of the “Five Ships”. The passage to France was a tragic one. His eldest son, Marin, would die aboard ship somewhere in the Atlantic Ocean. While the rest of the family would make it to Saint-Malo in France, Charles and his youngest son, Alexis, would die from the effects of the journey in hospital on 11-Mar-1759 and 18-Mar-1759 respectively. The passing of the three Guérin males would mark the end of this strain of the Guérin line, at least in name.

Epilogue: Naught But Tradition Remains

By the time of the deportations of 1755 and 1758, the descendants of Jérôme Guérin were, while not numerous by typical Québecois or Acadien family standards, numerous enough. The early passing of François left a widow and four children behind with only one son among them to continue the family name. Jérôme’s five sons, and their sons as well, seemed well suited to allow the Acadian Guérins to plant strong roots in North America. Cruel, perfidious necessities put paid to the notion.

The five Guérin men had six sons among them. As they and their wives were still young, it was possible that more sons could have been born to them had events turned otherwise. As it happened, only two more sons would be born, and those in France.

The Fate of the Guérin Name

Being of patrilineal culture, the fate of the Guérin name rested with the fates of the male descendants of Jérôme Guérin. Of the five sons and ten grandsons of Jérôme, we know the following…

Pierre Guérin and his wife seem to have passed away within the six years between the 1752 census and the expulsions from Île Royale. Only their children are listed in the rolls of arrivals at Saint-Malo. Of the sons, Pierre and Louis, both survived and eventually made their way to the port of Lorient and became sailors. Neither married nor had issue (as far as history tells us), ending this strain of the Guérin line.

François Guérin and his entire family died at sea when the Duke William sank off the coast of England in a winter storm.

Charles Guérin had his two sons had passed by 18-Mar-1759. Marin, aged 5 years old, died at sea, while Charles and his 7 month-old boy, Alexis, died in hospital within a week of each other soon after their disembarkation at Saint-Malo, ending this strain of the Acadian Guérin line.

Dominique Guérin and his son, Joseph, both disembarked at Saint-Malo. While Dominique and his wife, Anne, would have three more children in France who would survive to adulthood, all three were daughters, leaving only son, Joseph, to carry the name. While Joseph did get married to Agnès Pitre and migrate to Louisiana, they had two daughters, one of whom perished during the voyage back to North America. This line of the Acadian Guérins also ended.

Finally, the last, best chance for a continuation of the Acadian Guérin name was with the family of Jean Baptiste Guérin. Of him and his three sons, all save 2 year-old Xavier survived the crossing to France. Additionally, Jean Baptiste and his wife, Marie Madeleine Bourg, had two more sons in France: Joseph and Ambroise.

Of these four remaining sons, only Jérôme’s fate is known. He and his wife, Marie Pitre, made the journey to Louisiana in 1785. Infant son, Jean Pierre, seems to either have died en route or soon after their arrival. Their next, and only, child was a daughter, Marie Anne. The remaining sons may have stayed behind in France, but history is silent on their fates. Regardless, it would not be much of a stretch to say that the Acadian Guérin name in North America was probably terminated by La Grande Dérangement.

My Connection to the Acadian Guérins and La Grande Dérangement

François Guérin is not a blood relation of mine, as far as can be proven. According to some sources, he came from Martaizé, France. My blood ancestor, Claude Guérin dit Lafontaine, came from Lusignan, France, an hour’s drive away within the Poitou region. It doesn’t take much of a stretch of the imagination to consider the possibility that François could have been related to Claude. There is, however, a verified family connection to François via my Guérin family tree. Thomas Gearin, my grand-uncle, married Mary Parent, a direct descendant of François Guérin via his eldest daughter, Anne. Through that marriage, the Acadian Guérin bloodline merged with one of the Québecois ones.

Whereas none of the Acadian Guérins are direct ancestors of mine, I am a direct descendant of Acadian survivors of the La Grand Dérangement. Marie Modeste Doucet was born in Annapolis Royal on 16-Jul-1743 and was deported along with her family when she was 12 years old. She is my 5*ggm on my mother’s side.

Leur sang est le mien; leur mémoire est la mienne; leur héritage est le mien. “Their blood is mine; their memory is mine; their heritage is mine.”

Je me souviens. ![]()