Documentation is the neglected side quest of software development. Programmers and software engineers like to build logical solutions to digital problems. They don’t like describing their work, especially considering that the implemented solution usually required a plethora of changed plans and implementation dead-ends during the journey. For some, it’s also considered “busy work”. After all, the code describes the implementation, if you can read code. Why describe something twice?

The answer to that question, of course, is that other programmers need to understand the code and didn’t take the same intellectual journey that was undertaken during its development. The builder fully understands the house they built; the buyer does not.

Codoc: Code Documentation

The Codoc gem is a code file processor which reads specially-formatted code comments and can emit processed documentation items into a readable format, HTML, or into a package file for further processing. The name, codoc, is a double portmanteau for “code documentation” and/or “collaborative documentation”.

The idea behind codoc stems from my previous day job experience with a tool called doxygen as well as a Ruby development tool called yardoc and others. The core concept of codoc is not novel; the use of formatted code comments for documentation and other special purposes has been around for a long time. Where codoc differs is in its use of language specification configurations to support multiple source file languages in one tool.

For example, the yardoc Ruby tool relied on language introspection to process the Ruby source files and discern their use. It was a powerful tool, but limited to Ruby language implementations. I wanted to build a tool which offered similar working conditions in a variety of programming languages.

The Joys of a Language Agnostic

I am a full-stack software developer. I write server-side code, client-side code, browser-embedded code and local scripts. To serve all of my coding needs, I currently use Ruby, Javascript, C and, most recently, Objective-C. On the horizon are other languages, such has Swift and Crystal. I am fluent in these languages and I have a need to document them all.

Where codoc shines is its ability for language support expansion. This includes full support of language-specific jargon. For example, Javascript “throws” exceptions while Ruby “raises” exceptions. In each language’s configuration specification, codoc documentation in Javascript files will use the @throws comment tag while Ruby files will contain the @raises comment tag. This is an important design decision as programmers who are fluent in that file’s language should be comfortable writing documentation using the parlance of that language. Additionally, the post-processing code that generates the final readable documentation set should also use those labels. For example, Javascript documentation should describe exception conditions using the “Throws:” label while Ruby documentation should use the “Raises:” label.

This is not a How-To

As stated earlier, codoc documentation consists of formatted code comments. The format is similar to the following Ruby source file example:

## @file

## @author Kenneth F. Guerin

## @copyright Copyright © 2022-2026 Kenneth F. Guerin. All rights reserved.If the file was a Javascript file, the ‘##’ comment characters would be ‘//’ comment characters. This differentiation is contained with the language specifications.

Codoc documentation is processed into three levels of “blocks”: f-blocks, g-blocks and l-blocks. Blocks are begun with tags which declare the beginning of that type of block and subsequent information consists of bunched comments with different tags.

An f-block contains information that pertains to the entire source code file. An f-block is started with a “@file” tag with associated property tags such as @author and @copyright, as seen in the example above. Note that the @author and @copyright comment lines MUST immediately follow the @file tag line. No code or blanks lines or other whitespace can separate the “bunched” comment lines.

Data which follows the tag is tag-specific and, in some cases, optional. The @file tag, for example, can contain an optional “dialect” parameter, such as “// @file CRuby”. This comment declares that the C language source file being processed is used for implementing Ruby language features in C code. This dialect will allow codoc to include or expand the legal tag definitions to include Ruby language tags as, while the code is C, it is creating and implementing Ruby language constructs.

A g-block is a “global” object and is used to define namespaces, modules, classes, functions and the like, depending on language support. A Ruby example follows:

## @file

## @author Kenneth F. Guerin

## @copyright Copyright © 2025-2026 Kenneth F. Guerin. All rights reserved.

## @module Mill6Branding

## @abstract This module contains class definitions pertaining to Mill #6 branding.

module Mill6Branding

## @class Mill6Branding::Mill6Logo

## @abstract This class is used to build the Mill #6 logo.

class Mill6Logo

...

end

...

endThe example above illustrates the use of g-block definitions as well as the concept that g-blocks can contain other g-blocks. This is an important concept to allow for declaring objects within other objects or namespaces, if the language can support such constructs.

L-Blocks are used to document language constructs within g-blocks. In the example below, the class constructor is an l-block object within the class g-block. G-blocks can and will include l-blocks. L-Blocks, however, cannot contain other l-blocks. They have “local scope” and/or are leaf-nodes in the item hierarchy.

## @file

## @author Kenneth F. Guerin

## @copyright Copyright © 2017-2026 Kenneth F. Guerin. All rights reserved.

## @class DBase

## @abstract This class is used to read information from a dbase III formatted file.

class DBase

## @constructor

## @param filename [String] the name of the file to open

## @yields [DBase] sends self to an optional block for single-pass processing and auto-close <optional>

## @description The constructor creates an management point for dbase file access or spawns a single-pass file processing stream.

def initialize(filename)

return if !File.exist?(filename) || !File.file?(filename) || !File.readable?(filename)

@filename = filename

@io = File.open(filename, "r")

@header = nil

if !@io.nil?

load_header

if block_given?

yield self

@io.close

@io = nil

end

end

end

...

endIn the example above, note the use of “<optional>” within the @yields tag. Some tags can contain property specifiers. The set of legal specifiers and their formats are contained within the language’s configuration. Such properties are: <private>, <read-only> and <default: nil> to show that an item is private to a class or module, that the item is read-only or that the item, such as a function parameter, has a default value.

Again, this blog post is not meant to be a full how-to, but should serve to understand how codoc is used to define and process embedded documentation within source code files.

The Docs Application

Like the other applications that I’ve written developed, the Docs application is built within the Crux application framework. It is a storage and serving methodology for documentation sets. It currently supports two types of documentation: codoc doc packages and color tables.

One of the emitter formats that the codoc gem provides is a “docpkg” format. This format is designed to be stored and served by the Docs application. When downloaded from the server, the Docs application will format the contained information into an HTML page to be contained within its own UI tab.

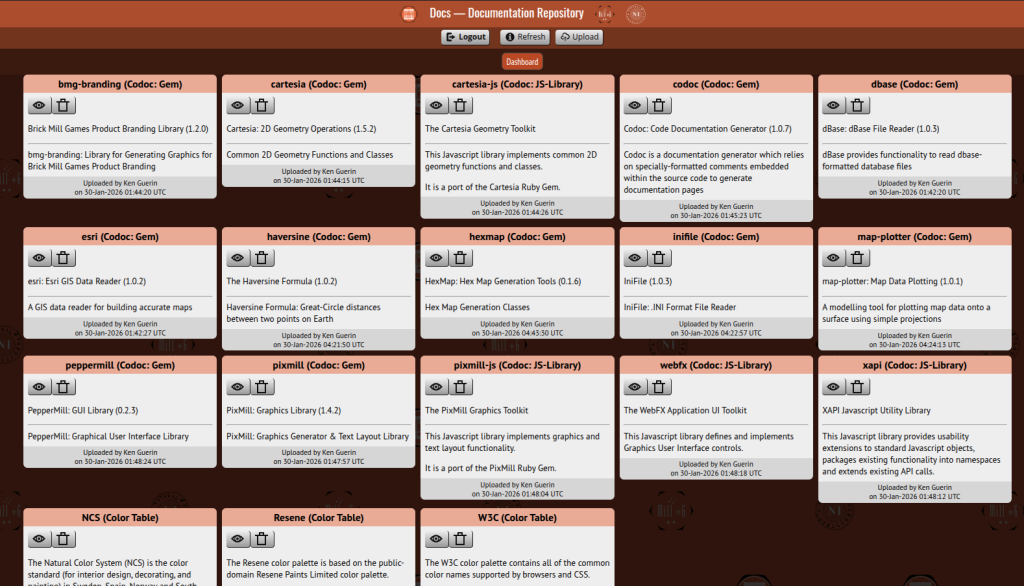

In the screenshot above, one can see fifteen codoc docpkg sets and three color tables in the user’s dashboard. Each display card presents the name of the documentation set, its type, a view button, a delete button, title and description information as well as upload statistics. As I have documentation editor privileges within the app, I can upload and delete documentation sets. Other viewers will only be able to view.

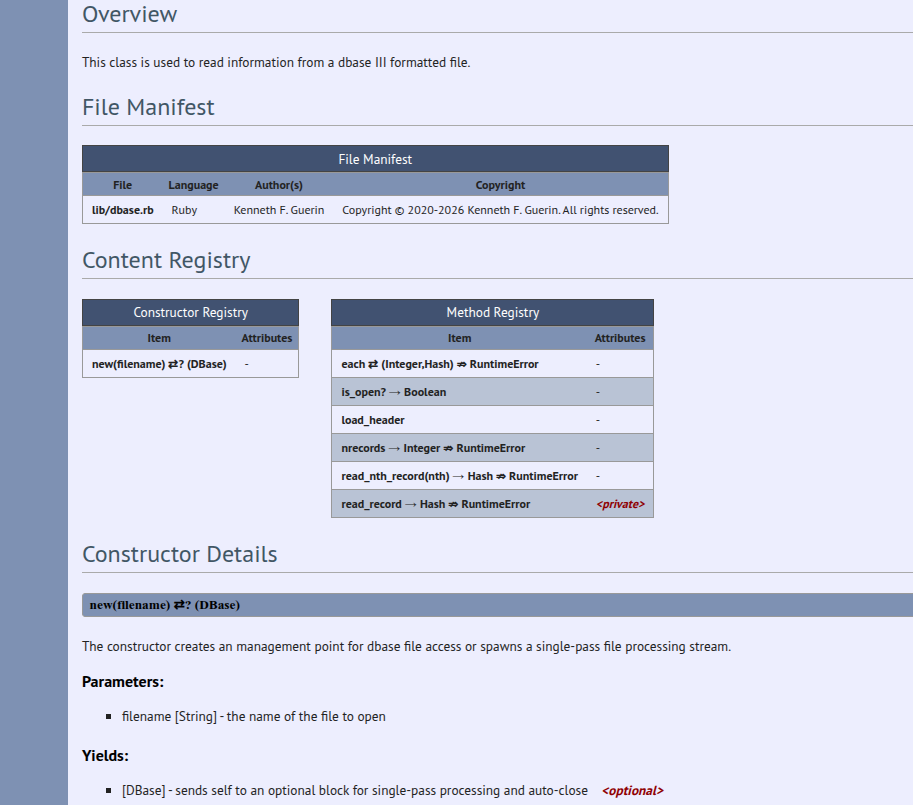

Viewing a codoc docpkg documentation set will reveal its initial Overview page in its own tab. The overview contains a file manifest of all files within the library or gem or other multi-file organizational construct. The contents directory will contain a manifest of g-block items and l-block items, each clickable to open a more detailed page. On the sides of all pages in the documentation set is a sidebar which allows for easier page navigation.

Note the colorized, italicized markers next to each item in the sidebar and Contents Directory. These tags will tell the user what type of object they are: C for class, M for module (g-block) or method (l-block), etc.

Navigating to a more specific page, such as the DBase class, will reveal more detailed information. The File Manifest in these pages will provide a subset of files which pertain directly to the object in question. Most of the time, these manifests will contain single files. However, for some types of items, such as modules which might have other items contained within their scope, more than one file could make up that item’s manifest.

Underneath, the more specific l-block items will be contained within typed registries and detailed information will follow.

Color Tables

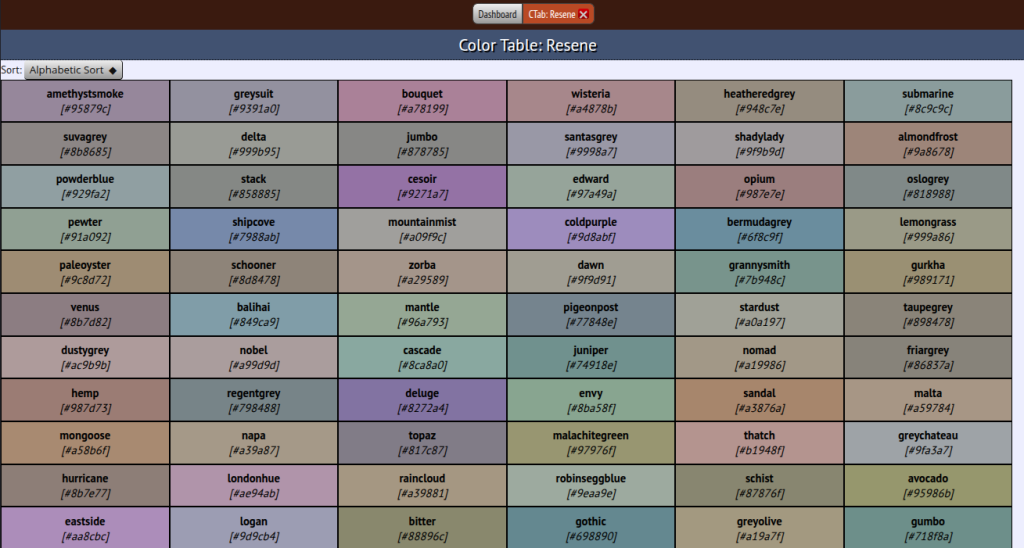

As stated previously, there are other types of documentation. When doing front-end work, choosing a color can be very important.

The ability to browse named colors within a palette is an important tool to have on hand. The Docs application can store color table specifications and allow the user to browse that table. Not shown, but implied by the sorting button in the upper left of the image, is the ability to do color sorting around a particular color by selecting an option with the menu button or by clicking on a color entry within the table.

The following screenshot shows the Resene color table sorted around a color named amethystsmoke.

More to Come

I know this post barely scratches the surface of the Docs application and the associated codoc gem library. More detailed posts may follow as more capabilities and documentation types become supported.

As always, stay tuned…

Postscript

The icon and color scheme for the Docs app was inspired by the “wall of VAX documentation”, a literal wall of orange loose-leaf binders which Digital Equipment Corporation would provide to its VAX/VMS customers back in the day.